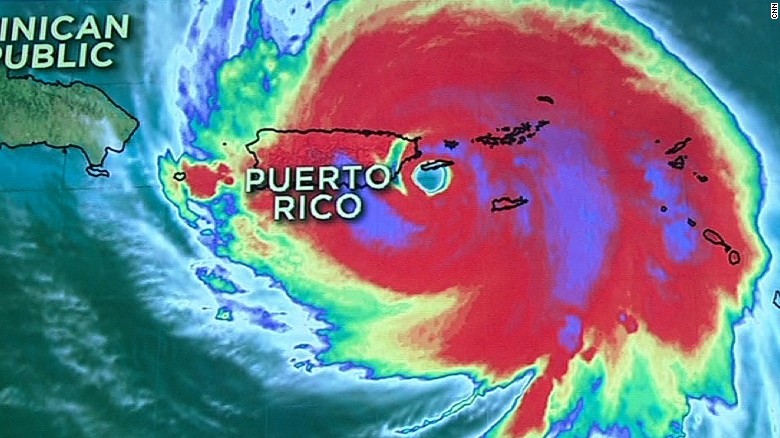

A humanitarian crisis

As I write this the American citizens on the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico are suffering from a major humanitarian crisis. Hurricane Maria struck the island nearly ten days ago and as of today the vast majority of the population is not only without power many, especially in more rural areas, are critically low on drinking water and food. Puerto Rico’s power and transportation infrastructures, already seriously compromised by previous storms this season and by a chronic lack of both human and financial resources, are broken.

of both human and financial resources, are broken.

Mayor Carmen Yulin Cruz of Puerto Rico’s capital city has appeared on national media begging that bureaucratic ‘red tape’ be cut so that aid can get to not only her city but to the entire nation. One massive logjam is tied to The Jones Act, a century old regulatory law for Puerto Rico requiring that goods shipped between U.S. ports be carried by U.S.-built vessels crewed by U.S. citizens. Nearly 10,000 shipping containers filled with essential aid have been languishing in port. As of today (28 September) our president has eased this restriction finally allowing this critical aid to flow more easily.

According to Mayor Cruz there are many examples of how layers of protocol and bureaucratic ‘red tape’ are hindering what have become life and death for Puerto Rico’s 3.7 million residents.

I am following this event closely not only because I am a fellow American but also because as a sociologist studying and researching the humanitarian aid industry I am seeing in real time some of the dynamics that have appeared in the responses to other ‘natural’ disasters around the world.

‘Natural disasters’?

The oversimplified dichotomy ‘natural disaster’ and ‘human-made disaster’ must be questioned on several levels. That this hurricane season is historic is a matter of fact, and that the magnitude and frequency of these storms appears to be  linked to human action induced climate change -specifically warmer waters that provide more energy for these storms- is doubted by only a few. Maria is ‘natural’, yes, but her strength is ‘unnatural’ and caused by what humans have done (or, in many cases failed to do). How aid is being delivered -or not delivered- since Maria moved north is adding to the disaster. Delivery of aid in many forms is hindered due to an array of logistically challenging circumstances, to be sure, but human avarice, incompetence, and yes even racism must be considered as factors.

linked to human action induced climate change -specifically warmer waters that provide more energy for these storms- is doubted by only a few. Maria is ‘natural’, yes, but her strength is ‘unnatural’ and caused by what humans have done (or, in many cases failed to do). How aid is being delivered -or not delivered- since Maria moved north is adding to the disaster. Delivery of aid in many forms is hindered due to an array of logistically challenging circumstances, to be sure, but human avarice, incompetence, and yes even racism must be considered as factors.

Paul Farmer has referred to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti as “acute on chronic” meaning that the quake itself was like a blow to the head to an already health-compromised cancer patient. In the case of Maria, this storm was the acute event but must be seen in the context of an already weakened island territory.

Square peg in a round hole

How do the local actors -be they government officials like Mayor Cruz, community leaders, staff of local NGO’s, local staff of INGO’s etc.- deal with the complicated and sometimes convoluted world of log frames, assessment tools, accounting protocols, chains of communication demanded by the organizational structures who control the resources that are intended to help their affected communities? How do the immediate and life-or-death needs of the affected community get addressed in a timely fashion when there are laws to follow and forms to fill out?

Sometimes rules need to be broken in order to save lives and restore dignity, but given the asymmetrical power dynamics that are very apparent in this situation, the default is to kowtow to the external actors -in this case the US government and large INGO’s who are responding- and follow laws and protocols.

From the particular to the general

I have been reading, researching and writing about ‘localization’ of aid and about local aid workers. I know that many local aid workers -local actors- are frustrated by the situation described above. As a sociologist looking in on the dynamic, what I see is a chronic and perhaps unavoidable clash between the local organizations that seek immediate concrete actions and external organizations (governments or INGO’s) that are burdened by accountability structures that make them inherently slow and frustrating to deal with. As Wall and Hedlund put it “….the humanitarian system is in theory already committed to locally-led responses, but this rarely translates into practice. (p. 7)”

More soon. You can reach me here.

Follow

Follow