The real versus the ideal

Some context

In my very first professional presentation as a sociologist I made use of the anthropological terms “ideal culture” and “real culture” in describing the huge gap between the published/public statements on how tenure and promotion judgements were supposed to be made and how they were made. The “ideal culture” as it existed in university statements regarding criteria for tenure and promotion were very far from what I collected in dozens of extensive interviews with faculty and department chairpersons in terms of the operative criteria, i.e., the “real culture.” No big surprise there for any academic. I have always been interested in this gap between what we say and what we do, the ought and the is, and so as I have pored through our survey data I was taken aback by how extreme some of the gaps appeared to be. I will claim no deep insider insights into the aid industry -like my co-author J can legitimately make- but in any case methinks our data indicates a problem which deserves -and needs- to be further described, analyzed and at various levels processed and addressed.

Data!

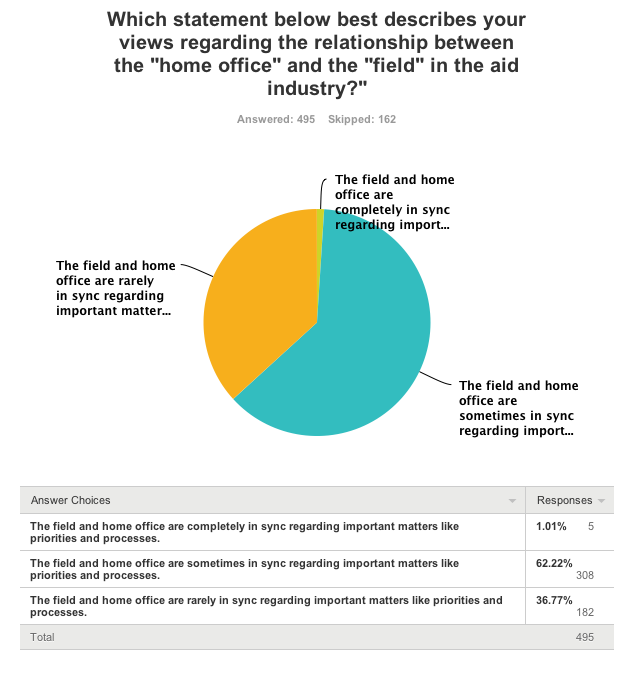

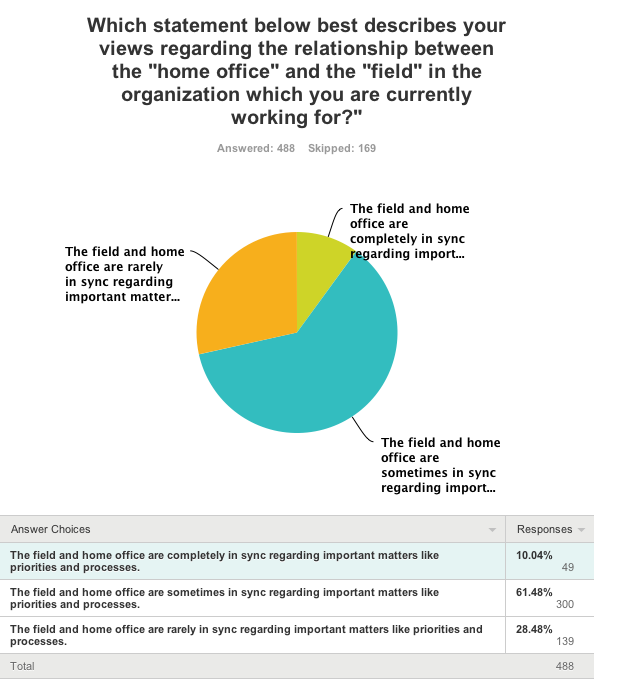

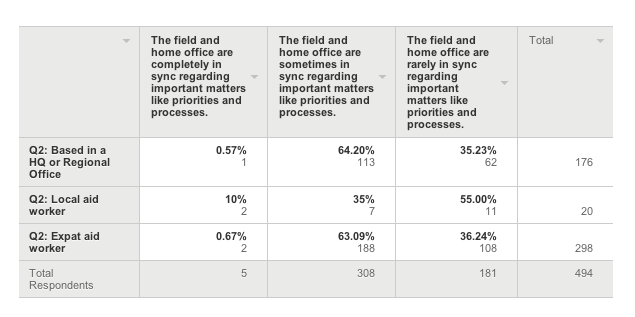

Let’s start with some data from the survey. In response to the question (Q50), here are the results to date.

Here is what some said in the open-ended response section regarding Q50 and Q51:

- There is often a large disconnect between the two and while field offices are more intent on doing, HQ’s can often be more intent on process – usually implementing systems which are time heavy and not that useful for the field. Field offices can see HQ management/advisors as pestering, and HQ’s can see field staff as renegades. However, having one good liaison officer between the two can make all the difference, ensuring better relationships and better outcomes for both.

- When an organization is large, as is the one I work for, many initiatives have a top down approach. The home office I work for often strives to understand the implications but realise that many of them are unrealistic from what we know from the field office. Thus, the requirements we are aware of and the reality that we know often don’t line up.

- Home offices are dwelling in idealism and bureaucracy. They see the big picture, which might sound positive, however often it’s important e to see the small picture. Sometimes, the smaller it is the better. This is exactly where the main issues are closer to the eye, inspected carefully and well understood.

- Many in ‘home office’ have not had any ‘field’ experience and therefore have little or no concept of what conditions are like. A bad day in Sydney is missing a bus. A bad day in the field is being shelled, or watching people die.

- There is a disconnect between workers in the field, experiencing and seeing individual issues and struggles first hand, and those that control the purse strings. Home offices seem to be much more bogged down in the politics of aid and humanitarianism, whereas field workers don’t care about the politics, just the work.

- The two ‘realities’ are often widely different and it can be difficult to communicate one to the other. The pace at which ‘field’ functions and the daily pressure they face often mean that their priorities and processes are not going to be as aligned as they should with the ‘home office’ which doesn’t face the same pressures and operates at a slower pace.

Follow

Follow