“In contrast to those who suggest that we act as soon as the whistle blows, I suggest that, even before the whistle blows, we ceaselessly try to know the world in which we live — and act. Even if we must act on imperfect knowledge, we must never act as if knowing is no longer relevant.”

– Mahmood Mamdani, Saviors and Survivors (p. 6)

More on Confronting Toxic Othering and Critical Hydra Theory (CHT)

[Note: Content from this post may be updated regularly to be used in a revised edition of my recent book Confronting Toxic Othering.]

Ethnocentrism

In conversation with a veteran humanitarian worker, I listened to her vent about a recent deployment to a major conflict zone. She noted that ‘ethnocentrism be damned’ there are some fundamental wrongs embedded into the local culture, using as an example the grotesque mistreatment of women and the use of rape as a weapon of war. Social scientists tend to preach that ethnocentrism – viewing and then judging one culture through the lens of your own- is inherently wrong, and in most cases it is.

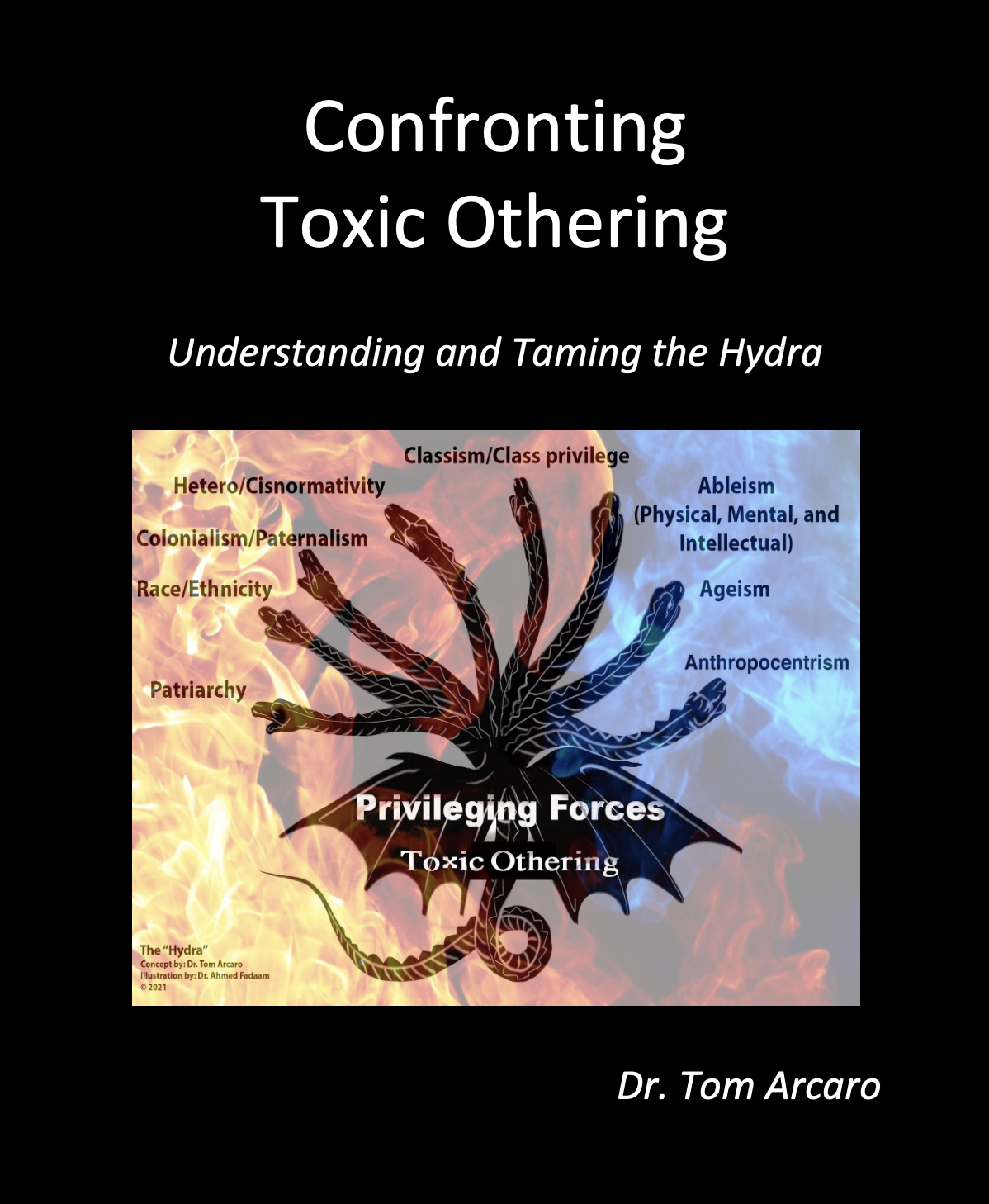

But there is nuance to add as we consider using critical Hydra  theory (CHT). Through this lens virtually every modern culture has norms, laws, policies, and even ideologies that justify and normalize the systemic marginalization of various groups within the culture. CHT demands a systematic and rigorous interrogation of all forms of marginalization made possible by the many privileging forces used by those in power to justify this marginalization.

theory (CHT). Through this lens virtually every modern culture has norms, laws, policies, and even ideologies that justify and normalize the systemic marginalization of various groups within the culture. CHT demands a systematic and rigorous interrogation of all forms of marginalization made possible by the many privileging forces used by those in power to justify this marginalization.

Employing the encompassing tool of CHT, to look closely at any culture is to identify multiple and egregious ‘baked in’ cultural practices that defines some of the members of that culture as inferior.1 The CHT thinker must be able to take a ‘long view’, realizing the process whereby marginalization has been ‘baking in’ to a culture goes back not decades but more likely centuries or even millennia.

The normalization of marginalization

Sociologist Diane Vaughn coined the phrase “the normalization of deviance” in order to help her describe in great depth the series of acts of deviance which ultimately led to the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. The phrase is explained here:

“The normalization of deviance occurs when actors in an organizational setting, such as a corporation or a government agency, come to define their deviant acts as normal and acceptable because they fit with and conform to the cultural norms of the organization within which they work. Even though their actions may violate some outside legal or social standard and be labeled as criminal or deviant by people outside the organization, organizational offenders do not see these actions as wrong because they are conforming to the cultural mandates that exist within the workgroup culture and environment where they carry out their occupational roles.”

Understanding the task of Critical Hydra Theory

In modern cultures, false consciousness -a lack of a clear understanding of the forces of oppression and marginalization at play in the culture- tends to be endemic and, by definition, unrecognized by most. Outsiders, e.g., expat humanitarian workers, can see these forces of oppression and marginalization more clearly. Ironically though, most of these outsiders would be unable (or unwilling?) to clearly identify these same forces at play in their own culture.

Just as with critical race theory (CRT), to employ CHT most effectively and legitimately one must

- be clear about their own positionality relative to all eight heads of the Hydra/privileging forces and, importantly, the shifting nature of this positionality in various social settings

- understand the fact that most -especially those (like me!) who are objectively privileged in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, nationality- must make extra efforts regarding their positionality

- must embrace the constant journey toward a deeper understanding of their own levels of false consciousness and about their role as oppressors and contributors to the continued normalization of the marginalization of others

- be capable of seeing the world as a whole using a perspective that is both global and also deeply historical

- understand that in an increasingly globalized world economies and even ideologies are seamlessly interwoven and critiquing one culture necessarily means commenting on an emerging pan-cultural reality we all share; ‘fixing’ one culture in isolation is a misguided goal

- seek ways to confront toxic othering at both the personal and cultural levels

Grappling with these challenges, we can all learn from thinkers like Paulo Freire who in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) uses the term ‘decolonizing the self’ as a way of addressing the phenomenon of false consciousness and goes further to argue for the comprehensive decolonization of all oppressed cultures, a theme expanded on in detail more recently by many writers e.g., post-colonial theorist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in his Decolonizing the Mind.

Perhaps most importantly, those who would embrace CHT need understand and learn from the methodologies of critical race theory (CRT), particularly as employed by thinkers such as bell hooks and of course Kimberlé Crenshaw, co-founder of the African American Policy Forum.

Being a deviant

We must all remain ever vigilant regarding our tendencies toward toxic othering, however unintended or culturally accepted. Make no mistake, using CHT properly involves the courage to deconstruct one’s past cultural learning and socialization and to look critically at oneself and one’s culture. This means, almost by definition, acting and even being an outsider to one’s own culture, that is, being a deviant. In this case though, the role deviant is positive, modeling behavior for others how to confront toxic othering in all its manifestations. Recalling the Latin proverb that says ‘in the land of the blind the one eyed man is king‘, just the opposite, those who see more clearly cultural faults may more likely to be seen as pariahs, and carry the burden of unfair stigmatization that those who seek true justice have always endured.

As anthropologist Jules Henry put it so long ago, “To look closely at our culture is to grow angry and to anger others.”2

Always seeking to know the world more clearly

In the end, many will make the lazy mistake of being just ethnocentric -critiquing other cultures- without doing the work of more clearly understanding the history behind deeply embedded norms, policies, laws, and cultural practices that gave rise to and continue to support marginalizing forces. Having the intellectual energy and time to engage with CHT is in itself a privilege, a luxury. But it is also our duty as humans -as students, teachers, humanitarians, etc.- to always seek ways to know the world in which we live and act more clearly and to recognize our own place vis-a-vis forces of oppression rooted in toxic othering.

1I wrote about this general idea many years ago; see here for my essay ‘Humanism, Feminism, and Cultural Relativity: Contradictions and Ambiguities”.

2See Henry’s 1963 book Culture Against Man, an ethnography of his own American culture.

Follow

Follow