“In any case, these interrelations between the three communities, all with different cultures and nationalities, proved that there exist people with a sincere understanding of other people, no matter where they are in the world. It proves that there always exist significant people who transcend government ideologies.”

–Behrouz Boochani, A Letter from Manus Island

COVID-19 response: ‘acute on chronic’ for the entire humanitarian sector

8 minute read

[Updated 4.7.20;5:20PM EST]

A global crisis

The humanitarian sector is reacting to a massive ‘acute on chronic’ situation as the COVID-19 pandemic impacts all aspects of ‘normal’ humanitarian work. UN entities (e.g., IOM, WFP) and all major INGOs scramble to react to this viral tsunami and to coordinate response with each other, major donor entities, and with affected governments on all continents. Supply chains are strained or broken, funding is even more uncertain, and affected populations are in varying states of even more extraordinary duress. Refugees and IDPs, especially those in camps behind guarded fencing, brace for what could be devastating outbreaks.

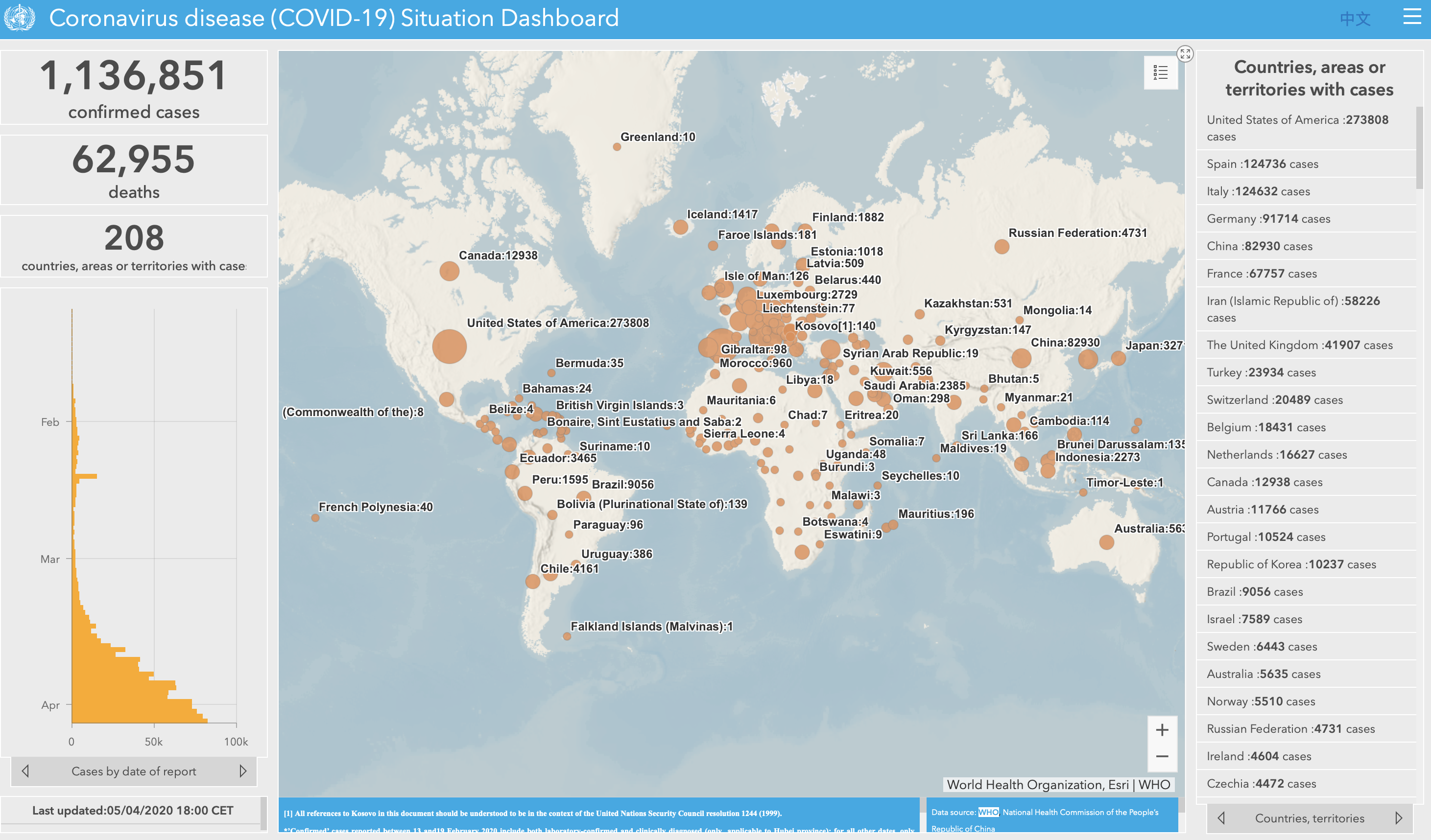

As I write this, the World Health Organization reports over 1,136,851 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and every projection I have seen guarantees the numbers will rise precipitously in the coming days, weeks, and even months.

Forecast modeling done just over a month ago put estimates at anywhere from 550,000 to 4.4 million cases globally. According to writer Tomas Pueyo, we are still in the ‘hammer phase’ where strong, enforced governmental actions

designed to slow the spread of the virus must be put in place to be able to ‘flatten the curve’ and minimize both human and economic loss. Here in the US in my home state of North Carolina, Governor Cooper put in place a 30 day ‘stay home’ order, allowing only ‘essential personnel’ permission to travel. He was urged on by hospital administrators who are trying to keep our state from entering a crisis phase such as in New York City.

As of now, of now the United States now has more cases than any other nation, and the numbers will rise quickly in near future.

Acute on chronic

I first encountered the phrase ‘acute on chronic’ reading Paul Farmer’s Haiti After the Earthquake. With this short phrase he accurately describes the impact of the 2010 earthquake on Haiti: acute on chronic, a sudden, violent shock on a population already compromised by long term poverty and political instability. At first I thought this phrase was a good description for what is happening globally relative to the COVID-19 impact, but at a deeper look ‘acute on chronic’ seems too flat and unidimensional to capture all that is happening in various contexts around the globe. In places like Syria and Myanmar where there are active conflict zones the situation is exceptionally complicated, and the affected communities are suffering in ways that defy description. Perhaps acute on acute on chronic is more accurate, but that still seems to fall short of an accurate description.

COVID-19 alone is bad, but the short and long term economic impacts of the necessary social distancing have led to a global economic meltdown which some are calling the worse economic situation since the Great Depression in the 1920′ and 30’s.

A view from ‘the field’

How are humanitarians feeling about what this rapidly morphing global event? Here is one data point, a view from a national humanitarian serving in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh:

“When COVID-19 was detected in the world people [here] became curious and concerned about what is going to happen in Bangladesh. The first case was identified in Bangladesh on 8th March. After that tension and fear is felt everywhere, MSF staffs are not out of this; they are very much anxious about the situation. 80% of discussion of total discussion about COVID-19. Many staff are thinking that MSF should have taken [additional] steps when they heard. Some staff were concerned that we received expats and sent them to COX [refugee camps] , because it might cause the infection in the community. After March 17 MSF decided to bring all the expats under the 14 days quarantine before starting the work.

Anyway, fear is still running around the staff. In this situation, MSF asked the staff to have their choice whether they want to work or not. Everyone choose to work for 2 reasons. 1. Fear of losing job and 2. Working for humanity. As you know the supply chain in world is broken, so MSF is not out of this, but we always maintain eprep (emergency preparedness), so we collected some PPE and other materials from the Emergency Response preparedness cache.

MSF is ready to receive patients. MSF has prepared an Isolation unit and prepared an emergency team giving them proper training. MSF also gave training how to use the PPE and other [equipment] in an efficient way. MSF doesn’t have facility to test [for COVID-19], but can collect samples and can send them to government facility for testing. So far I think MSF is still not allowed to collect sample but MSF is trying to get approval. Hopefully, MSF will get approval before the situation get worse.

I think we are facing another problem. The Prime minister announced that no refugees can come out from the camp. Our biggest hospital is out of the camp though it is close to the camp and we receive huge amount of OPD and IPD patient. I am not sure whether they will be stopped to come out or not to get general treatment.

The general situation:

People in Bangladesh are in panic as they don’t trust government statistics and their measures. Still they have only limited facilities to test COVID-19. They are not testing anyone who are complaining corona but are getting calls. Only eight phones are provided to complain about corona. If they get 4000 calls, they test only 100 among them. Some of the intellectual think government’s policy is ‘not test no corona’. Some people are dying with the symptoms with corona but they’re not in the statistics as they were not tested.

The other issue is countrywide lock down. Many people lost their job. Almost half of the people are day laborer who earn first, then eat. They are in serious conditions; they say, ‘we are not dying from corona but hunger.’ Today is 7 days of the lock-down, people are going out slowly, they are not caring about the ARMY and Police. They said, ‘give me food first, then ask me to stay in HOME.’ The government is giving some relief but it is very limited. I assume that it is about 10% of what people need.

So I am very concerned for other people that many casualties will be appeared in April.”

The people in Bangladesh are struggling to stay safe, but those already economically marginalized are having difficulty coping. The World Bank is pouring funds into Bangladesh, but there is uncertainty as to how broad an impact these temporary funds can have.

Long term positive impact: a ‘reboot’?

It is cliche -but perhaps true- that from crises there are lessons to be learned. And perhaps even in a sector whose raison d’ etre is responding to all manner of natural and human made disasters, new insights will be gained. But this pandemic just now in early April feels bigger and more daunting in its scope than any other single event our global culture has ever faced. Here’s how one veteran humanitarian put it,

how one veteran humanitarian put it,

“…the pace of work is crazy. I’m home but it’s one of the toughest deployments so far.”

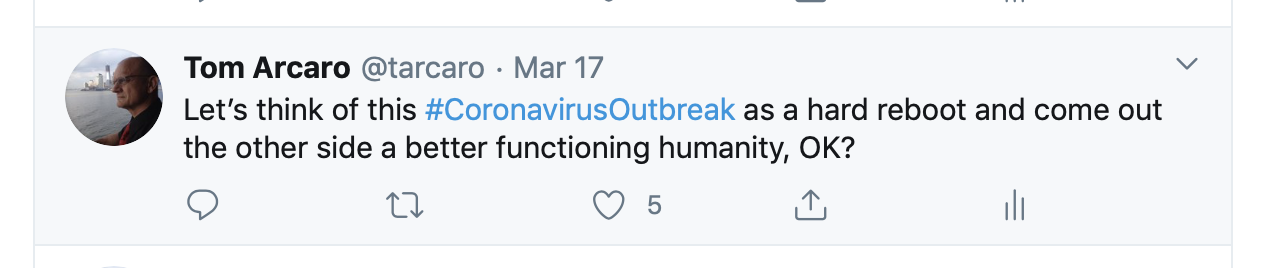

Many pundits assert that life post-COVID-19 will look very different, and perhaps thinking about the current situation as a ‘hard reboot’ of the global system can lead to some optimism. Can we come out the other side a better functioning humanity?

One primary lesson is that we are one human family, with all our sociocultural, economic, intellectual, and even spiritual lives intermixed, inextricably and permanently. You might be able to name a part of our social world that not impacted by this pandemic, but you’ll strain yourself doing so. Even if you do come up with an answer, think longer and you’ll likely see one.

Another part of this lesson is that our fates are all connected, and blind isolationistic policies are counterproductive. World travel is a given, and as far as pandemics go we are only as strong as our weakest link. In my own nation, one outcome of this pandemic may be that our leaders will see that universal health care is a must, and finally the US can join the rest of the Western world in recognizing health care as a basic human right.

Another lesson might be learning that capitalism and neoliberalism are ill-suited for responding quickly to pandemics. It is hard to monetize prevention and preparation. In the same vein, the disproportionate impact of this pandemic on the already marginalized -as described by the humanitarian quoted above- will serve to shed light on our dysfunctional and unjust global economic system that has pooled extreme wealth into fewer and fewer pockets.

A better functioning humanity

As for the humanitarian sector, post-COVID-19 it will be stronger, one hopes, but only time will tell. My view is that the biggest change needs to come in the form of much more aggressive funding streams, perhaps addressing the failing of the traditional systems. Prevention is key, but one wonders how events globally might have been different -and less fatal- had there been a humanitarian system with the flexibility and resources to immediately respond to outbreaks in various nations around the world.

A ‘better functioning humanity’ has a robust, competent, and professionally staffed pan-national response mechanism able to respond to existential threats, a UN on steroids, if you will. This entity I am imagining would effectively coordinate and deploy the many INGOs and national NGOs in response to global disasters such as pandemics. One step further, the nations of the world would see the wisdom in ceding some degree of sovereignty so that this mechanism could move swiftly and efficiently in responding to any global existential threat. A better functioning humanity will be just that, a global system that operates on the assumption that, to quote Paul Farmer once more, “Humanity is the only true nation,’ a world populated by, as Kurdish refugee Behrouz Boochani would say, “significant people who transcend government ideologies.” If we can imagine such a mechanism we can make it happen, right?

I won’t hold my breath.

Contact me with your comments or questions at arcaro@elon.edu

Follow

Follow