Updated 14 Feb 2019

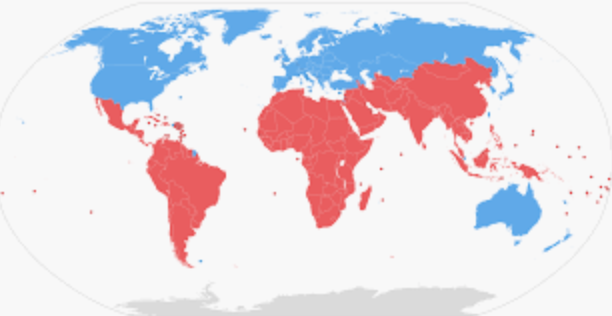

Where are humanitarians from and where do they work?

A question

My research into the humanitarian ecosystem in general, and more specifically into the lives of the humanitarian workers themselves, has lead me to many questions. In the context of this research, perhaps the most globally important questions concern where humanitarians are from and where they work.

In the context of assessing some of the promises made in the ‘Grand Bargain‘, this question is important because it probes into a significant indicator of ownership and agency.

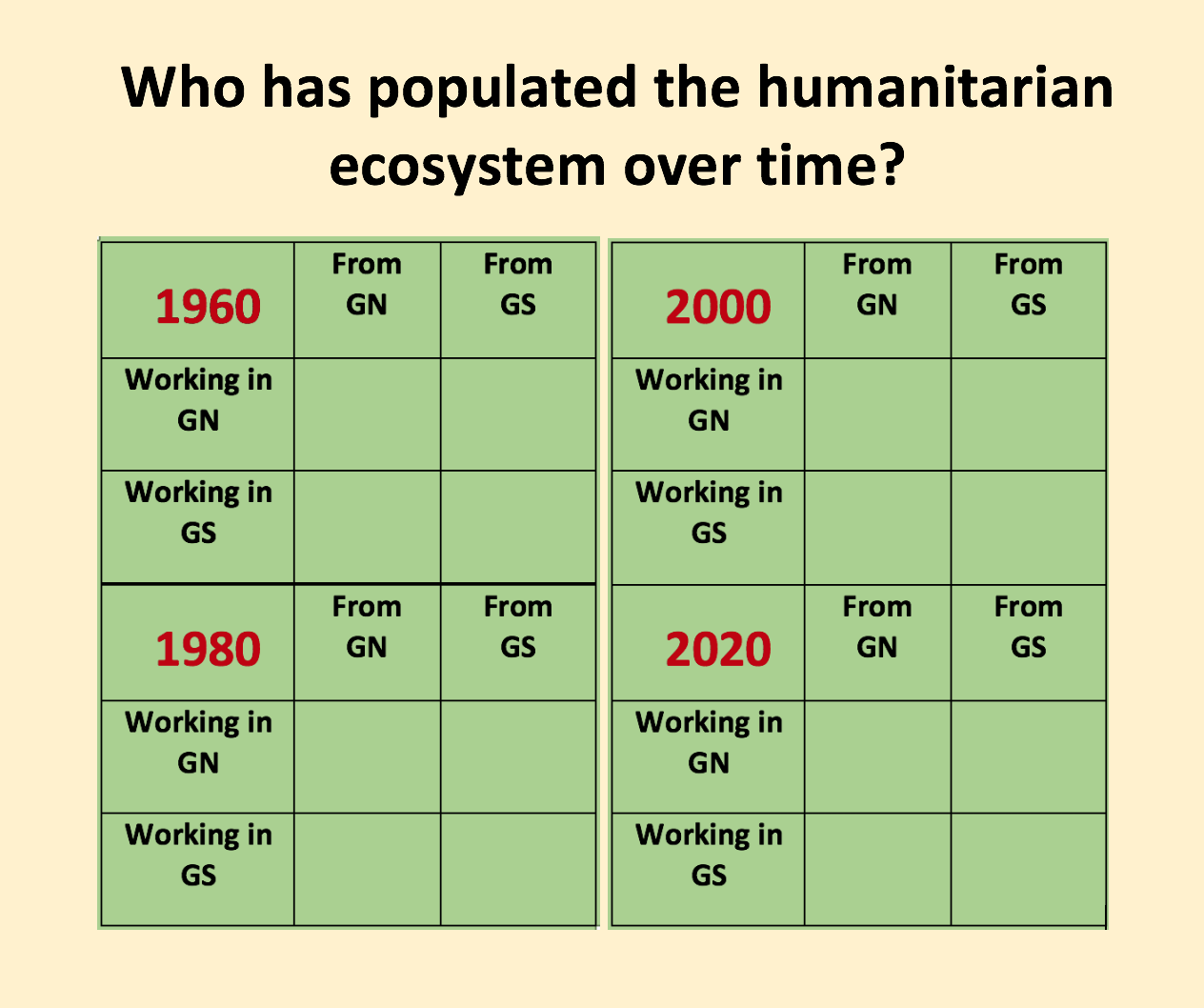

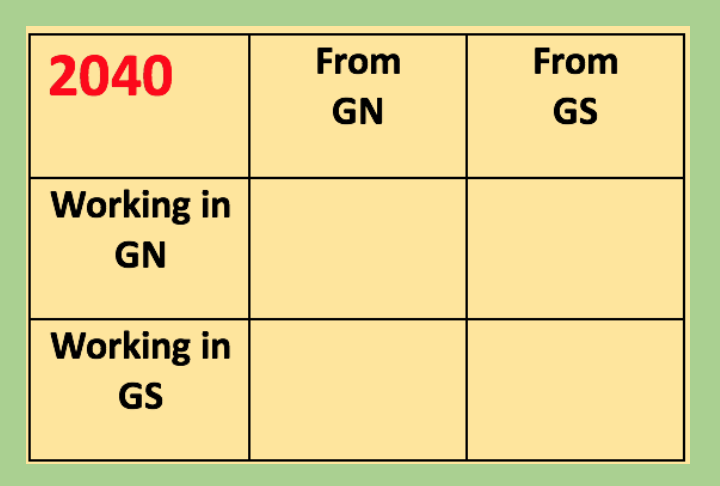

So, below is my question in table form, where GN = Global North and GS = Global South, and the intended goal is to have a percentage in each cell. For example, in 1960, we would need to know, based on the total number of people working in the humanitarian sector, what percentage are from the ‘Global North’ and work in the ‘Global South’, and so on.

So, below is my question in table form, where GN = Global North and GS = Global South, and the intended goal is to have a percentage in each cell. For example, in 1960, we would need to know, based on the total number of people working in the humanitarian sector, what percentage are from the ‘Global North’ and work in the ‘Global South’, and so on.

Laying this out is the easy part. Getting reasonably accurate numbers to populate each cell will be challenging, to say the least, especially for 1960, 1980, and, clearly, 2040.

Critical questions of definition

Looking at the above, many questions arise, some are matters of definition, and others more general in nature.

- What is meant by the ‘humanitarian ecosystem?’ Does this mean both emergency relief for both natural and human-caused disasters and development work?

- How does one differentiate between ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’? Why is that differentiation important? Read this excellent article by Canadian political scientist Marlea Clarke for both a history of the term ‘Global South’ and the current issues with usage.

- In the next 20 years, what geopolitical and climate change factors will impact the humanitarian ecosystem that might drive these numbers in one direction or another?

- How would these cells look if we added gender into the mix?

- What are the economic, policy, and larger sociocultural forces driving the change in percentages over the decades?

- What would be the ideal percentages in each cell, and why?

- How would percentages in these tables vary over time by region and humanitarian response?

- How would percentages in these tables vary if separated by natural disaster versus conflict responses?

How many humanitarians are we talking about?

From the 2018 State of the Humanitarian Sector (SOHS) report,

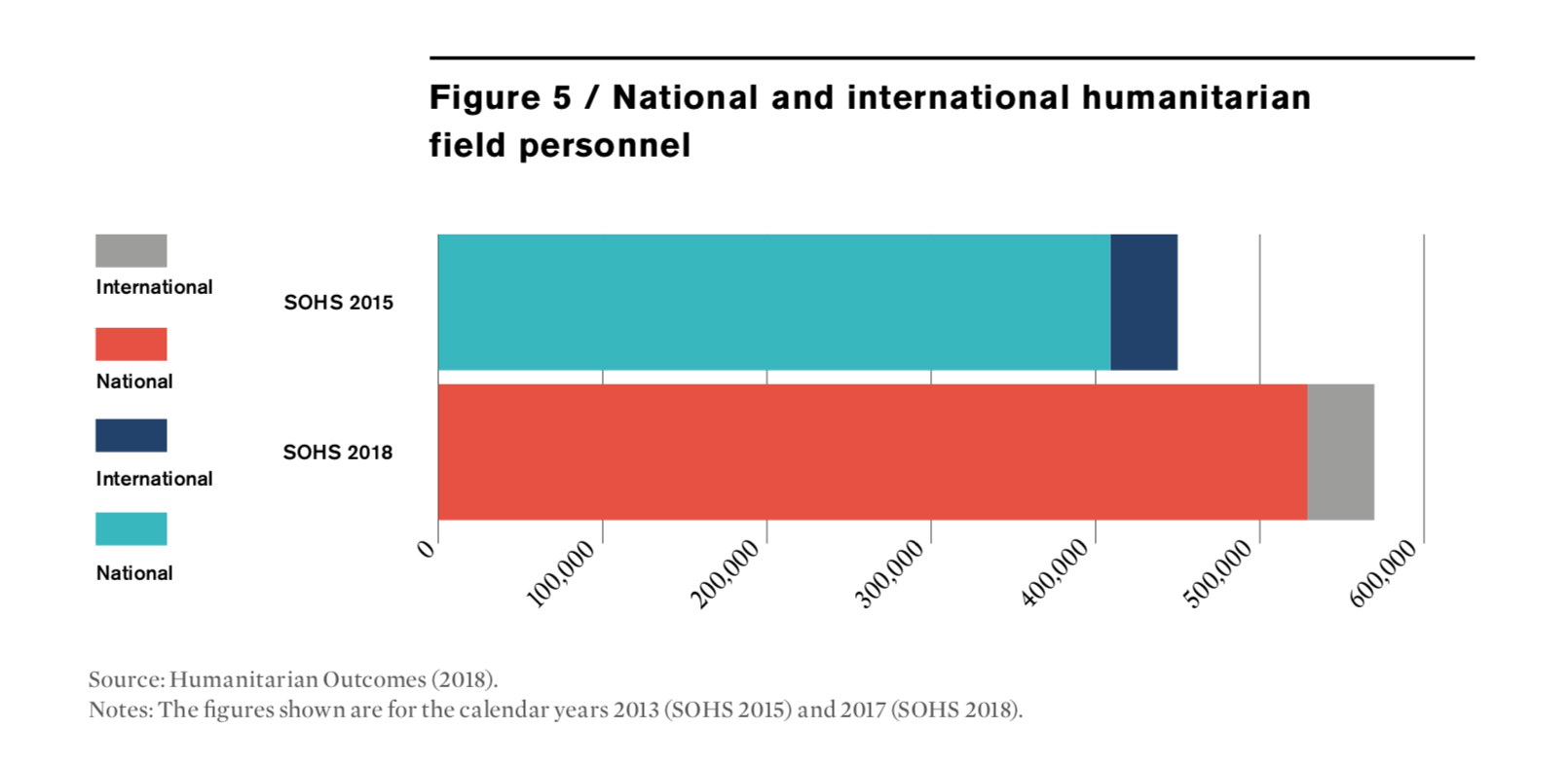

“By 2017, humanitarian agencies employed approximately 570,000 people in their operations– an increase of 27% from the last SOHS report (see figure 5). Growing numbers of national humanitarian workers appeared to drive this increase, while the number of international (expatriate) staff remained stable.

I think it is fairly safe to assume that the vast majority of national humanitarians -over 90%-are from and working in the Global South, the the ratio of national to international (expatriate) humanitarian staff is clearly trending toward an even higher percentage of national, and hence presumably Global South, staff. That over one half million humanitarians from places like Jordan, Iraqi, Bengali, Kenyan, and Ethiopia dominate the humanitarian sector is beyond the imagination of most outside the sector where the face of international aid is still that of men and women from Global North.

No answers, but one final and critical point

Yes, for now the tables above have no percentages, and I am not certain where accurate data exists to populate each cell. My sense is that, given some of the definitional issues with the overall question, filling in these tables with numbers will ultimately be a matter of ‘guestimation.’ We do know that currently an estimated 80%-90% of all humanitarians are from the Global South.

But even if the humanitarian ecosystem overall was populated 85%-95% by Global South staff, would that necessarily have an impact on the true dynamics within the sector? In the words of one female Iraqi LNGO worker,

But even if the humanitarian ecosystem overall was populated 85%-95% by Global South staff, would that necessarily have an impact on the true dynamics within the sector? In the words of one female Iraqi LNGO worker,

“It is not only the number… it is who is in decision making positions. We in Iraq could have 85% of the positions but not nearly that much power. The decision making power and the power to be creative is what is important…not just to say yes to whatever we are told… The percentage is important when you can make change and not just be a robot and implement what we are told.”

Numbers only tell part of the story, and at best they are crude indicators. At worst they are a smokescreen for ‘business as usual’ unless there is a real shift in power. The language in the Grand Bargain mentions, for example, “More support and funding tools to national first responders” but does not directly make reference to the power differential issue. This must be addressed, I feel, going forward.

Anecdotally, my experience in talking with students, colleagues, as well as those outside academia (friends, and family, etc.) is the stereotype of the humanitarian worker as being from the Global North and working to ‘save’ those in the ‘Global South.’ That this misconception persists is one of the factors that drives my research and writing; I seek to debunk this myth and replace it with a more accurate -and perhaps less racist- understanding of who populates the humanitarian ecosystem.

I invite my fellow researchers and humanitarians to consider the question(s) above. Contact me if you have any questions, comments, and/or suggestions.

PS. Yes, the color scheme of this post is bonkers. Sigh.

Follow

Follow