An aid worker voice from Cox’s Bazar

“Even the most extreme consciousness of doom threatens to degenerate into idle chatter. Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today.”

-Theodor Adorno

Prelude

I am reminded of two observations from James Dawes in his book That the World May Know. He states,

“Indeed, giving voice can also be a matter of taking voice.

“This contradiction between our impulse to heed trauma’s cry for representation and our instinct to protect it from representation -from invasive staring, simplification, dissection- is a split at the heart of human rights advocacy.”

The voice I report below speaks in the first person of atrocities cum genocide, this one excruciatingly experienced by the Muslim Rohingya in Myanmar (Burma) just in the last couple years. The blood is barely dry, some corpses not yet buried.

That said, I here now offer a trigger warning. The words and images below are exceptionally graphic.

Rohingya humanitarian

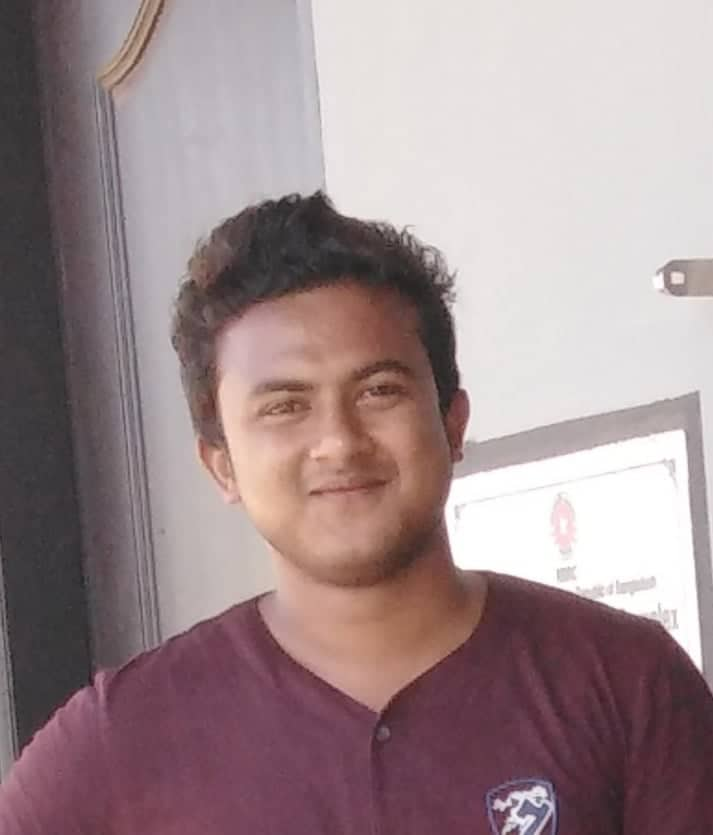

Like many humanitarians, Arif has made the transition from being part of the affected community to being an aid worker, in his case doing field monitoring and observation for DRC (Danish Refugee Council) in Cox’s Bazar and also serving as a mentor with Muslim Aid.

According to OCHA,

“As of March 2019, over 909,000 stateless Rohingya refugees reside in Ukhiya and Teknaf Upazilas. The vast majority live in 34 extremely congested camps, including the largest single site, the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Site, which is host to approximately 626,500 Rohingya refugees.”

Arif is a refugee, father, husband, humanitarian, and a poet.

His story is one that includes an all-too-common transition in his part of the world, going from a beneficiary to humanitarian. There is no way to know exactly how many of the 450,000 national humanitarians around the world have made this same transition, but that would be a telling bit of data. Among those, many have done the transition more than once, going from served, to server, and back to the served, then back again as climate change or continuing conflict (or both!) impacts her/his home population.

As a humanitarian, Arif’s job includes educating his fellow Rohingya about the aid being offered to them  and how to navigate their new life as now citizens of ‘temporary camps’ located in Bangladesh.

and how to navigate their new life as now citizens of ‘temporary camps’ located in Bangladesh.

Another aspect of his job is to help these refugees begin to live a ‘normal’ life, one that includes healthy (and, hopefully, detoxifying) exercise through athletic competition.

Below is a photo taken by Arif of teams in a volleyball tournament held in April of this year. Arif explains,

“The tournament was organised by the Rohingya youth committee just because to have a pleasure in order to expunge the traumatic shocks that were faced during genocide. In the pic, a female one is camp manager and her left side one is Camp in Charge as chief guest (Sheikh Hafezul Islam) were also present.”

Expression through imagry

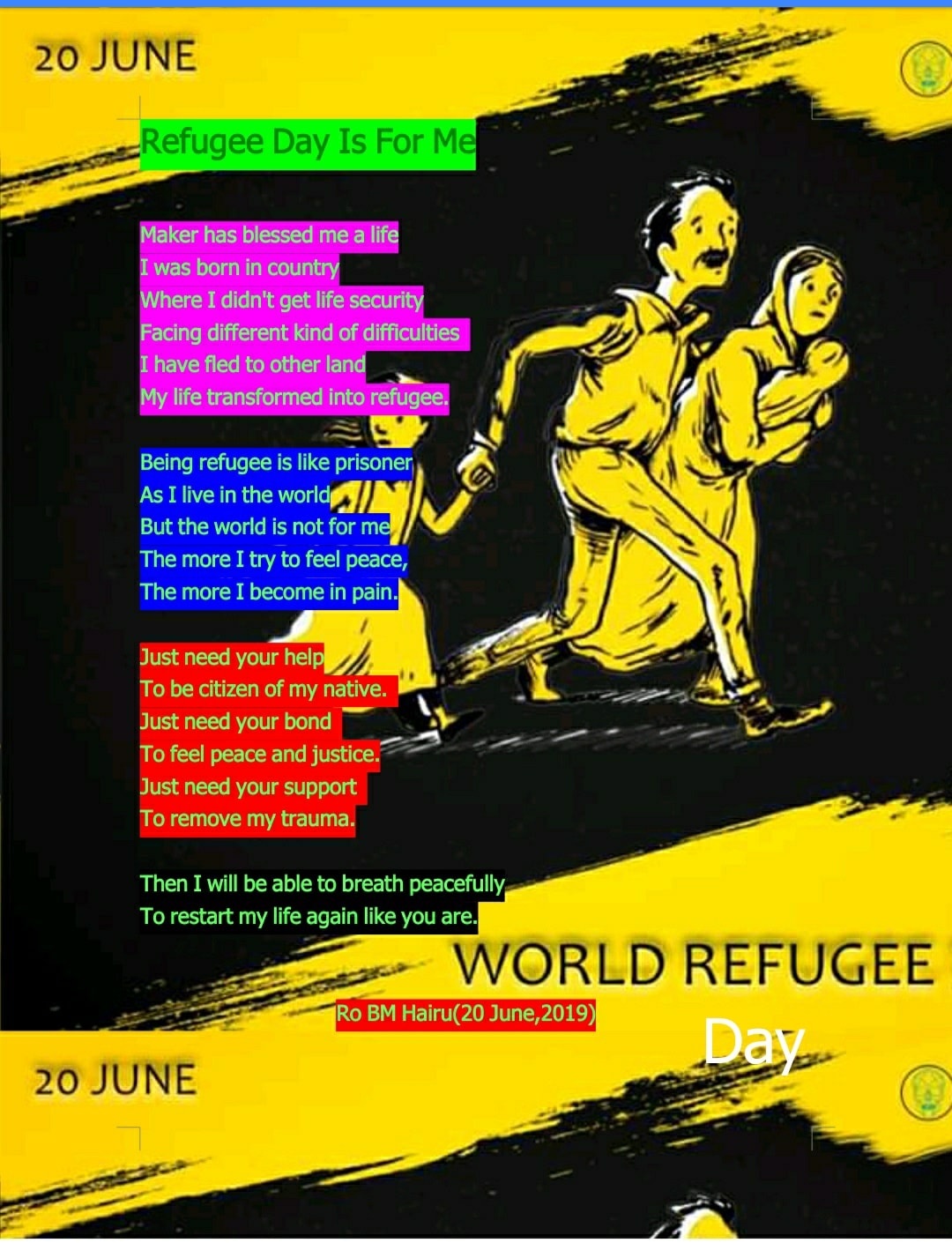

Poetry as a form of expression is as old as the written word itself, and recently has been used by many Rohingyan survivors not only to describe their experiences but as a form of activism as well. Some of this poetry is even brought to life in video as seen here on The Wall of Darkness. As a stateless people, the Rohingya lack formal political power. What they do not lack, though, is agency: the will and ability to articulate their views and to control their own destiny.

Arif has asked me to present his poem and accompanying images in the hope that the world may know what has happened. I asked him why he writes and also why he has become a humanitarian. He wrote,

“I write it just because to be a documentarian and to express the strong feelings of all the Rohingyas to [those people] all over the world that different kinds of persecutions such as gang raping, killing, burning down houses, shooting gun fires and everything on Rohingyas oppressed by unkind Burmese government. Being a humanitarian serving other Rohingya would be very valuable is like ‘magnanimous serving and a great humanity for the communities’ as a person without a heartfull humanity can’t be a good humanitarian aid worker.”

When pressed on why he wanted his poem and images published he said “so that the world may know what has happened.” Already shared with his friends on Facebook, here is his poem.

Ever Noteworthy Oppression

Oh, My dear brothers and sisters!

During the period of ethnic cleansing

Lost sleep of millions people as amazing

Nobody tried to escape from gang raping,

And killing of unmerciful Burmese military

But everyone should mind it as necessary

Oh, My dear brothers and sisters!

During the period of fleeing to survive life

Lost dignity and valuable things different type

None fled safely under ballistic missile shoot

War victims on famishing, and died without food

So, should never forget it till we are alive.

Oh, My dear brothers and sisters!

While crossing Naf river to Bangladesh,

Mass corpses were found on land, in mass grave,

And in bushes and floating on river without save

Nobody could perform the funeral like we do

Hence, Never make that “Out of sight out of mind”

Oh, My dear brothers and sisters!

Babies we’re snatched, thrown on burning fire

Some gave birth on vessel without maternal care

Rohingyas corpse became food of amphibians!

Traumatic events made hearts ever disappointed

As human beings, Never do that out of minded

Oh, My dear survivors and world activists!

Pogrom on us attacked by brutal Burmese military

That should ever keep in mind for our life history

Should’nt endeavor to forget four genocidal days,

People those we’re killed are human like us!

For real right, staying in tents Like a keyless cage.

Arif explains,

“I wrote this poem not only for remembering and feeling but also publishing to world wide that people can realize what types of persecution, oppression, torturing, gang raping and killing were done by Myanmar government on Rohingyas for our real human right.

They are written in English because it is international language and people in the world can read, realize, and feel easily about the poem. And my native tongue is Rohingyalish so it is only for Rohingyas but in school and college, all the subjects are studied and learnt in Burmese and English. It was not so hard for translating this poem of ideas and emotions into English because it was directly translated from Rohingya dialects to English language.

I hope people in the world will learn many things from reading my poem that how much violences and massacres was going to on us (Rohingya Muslims).”

Thoughts

There is so much to say about the above and just now I have trouble finding the words. Reading descriptions and seeing images is one form of bearing witness. I pause as I study the faces of Arif’s daughters. One question bubbles to the surface: what will their future hold?

That humans are capable to both acts spectacular beauty and those which are unimaginably grotesque remains the defining paradox of our species.

In his book Dawes asks, “What is the line that separates those who are merely moved from those who are moved to act? When does the story become real enough to change you?” Arif is a working humanitarian in the most literal sense, toiling daily just now to support Rohingya refugees, his brothers and sisters. But he is also a humanitarian in the more global sense, and through his poetry trying to both move people and also, perhaps, move them to act.

Post script

As a first year sociology grad student I was the teaching assistant for a sector of Introduction to Sociology. The professor, having earned the title “master teacher”, crafted a course designed to impact the students deeply.

Midway through the semester as we covered the requisite chapter on ‘race and ethnic relations’, the professor screened a short documentary for the 100 or so undergraduates, most 18-19 year old first year students. The professor did little to set up the viewing; this was well before the time of “trigger warnings”. Since I had not seen it before I was hit just as hard (perhaps harder, if that is possible) than our young students. The documentary, in French with English subtitles, was hard to watch and even harder to forget. In my case, impossible.

You can watch Night and Fog here and judge for yourself.

Sociologist and cultural critic Theodor Adorno, quoted above, opines, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Can one write poetry after Rwanda? or Gaza? And I wonder, inspired by @HamidDabashi, what Rohingya poetry can -and does- mean. But I do know that anthropologist Leslie White was on to something when he was asked the same question. In answer he said, simply, “We must.” Our very humanity is based on our deterministic need to communicate what we know and feel. To cry out when witness to atrocity -be it in paintings, poetry, images, or films- is in equal measure our duty and our destiny.

I’ll agree with another of Adorno’s observations. He says, “It would be advisable to think of progress in the crudest, most basic terms: that no one should go hungry anymore, that there should be no more torture, no more Auschwitz [or Gaza or Rakhine/Cox’s Bazar]. Only then will the idea of progress be free from lies.”

Bearing witness is one pathway to progress. Thank you, Arif.

Please contact me if you have and feedback, questions, or comments.

Tom Arcaro is a professor of sociology at Elon University. He has been researching and studying the humanitarian aid and development ecosystem for nearly two decades and in 2016 published 'Aid Worker Voices'. He recently published his second and third books related to the humanitarians sector with 'Confronting Toxic Othering' published in 2021 and 'Dispatches from the Margins of the Humanitarian Sector' in 2022. A revised second edition of 'Confronting Toxic Othering' is now available from Kendall Hunt Publishers

More Posts - Website

Follow Me:

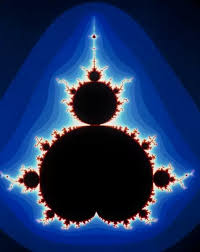

compensation compared to international staff, the refugee/humanitarian workers have essentially the same complaint relative to national staff. To get even more granular, it could be observed that the refugee/humanitarians get more compensation and benefits than other refugees, and so the pattern continues at different scales, not unlike a simplified Mandelbrot set perhaps.

compensation compared to international staff, the refugee/humanitarian workers have essentially the same complaint relative to national staff. To get even more granular, it could be observed that the refugee/humanitarians get more compensation and benefits than other refugees, and so the pattern continues at different scales, not unlike a simplified Mandelbrot set perhaps.

Follow

Follow