A (second) note on faith and aid workers

Overview

I recently presented and commented on our survey data relevant to faith and aid workers. Just before this post went live EvilGenius was putting out two mini-polls on that topic. As with our longer survey, many respondents were generous with their time and offered extensive and thoughtful comments.

EvilGenius asked first for the respondent’s views on the net impact of religion as a force for good or bad in the world. Though this question is clearly very complex, there is precedent for asking it. The Tony Blair vs Christopher Hitchens debate that took place in Toronto, Canada back in 2010 examined the same question, specifically, “Be it resolved, religion is a force for good in the world”.

EvilGenius asked first for the respondent’s views on the net impact of religion as a force for good or bad in the world. Though this question is clearly very complex, there is precedent for asking it. The Tony Blair vs Christopher Hitchens debate that took place in Toronto, Canada back in 2010 examined the same question, specifically, “Be it resolved, religion is a force for good in the world”.

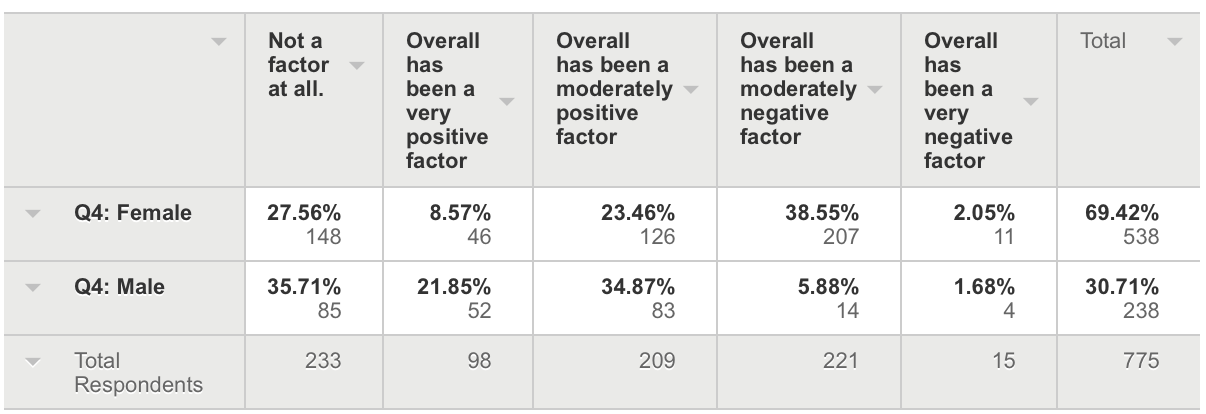

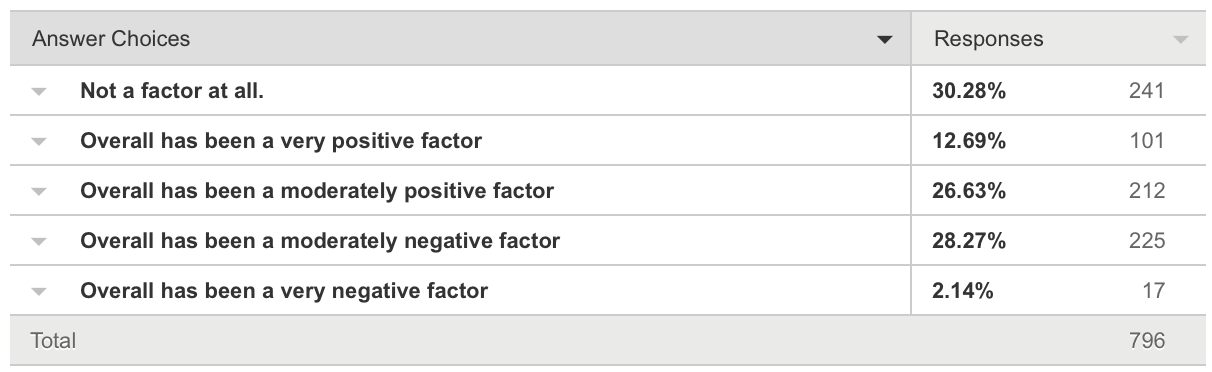

The second mini-poll is a bit more specific and probes into the question “does being faith-based impact the efficacy of aid organizations.”

I’ll present some data on both of these questions and then conclude with some observations of my own. Please note that the response rate to both of these mini-polls was low and we are very interested in more viewpoints. If you are reading this and have not yet take the polls please do so now. Each is here and here and below.

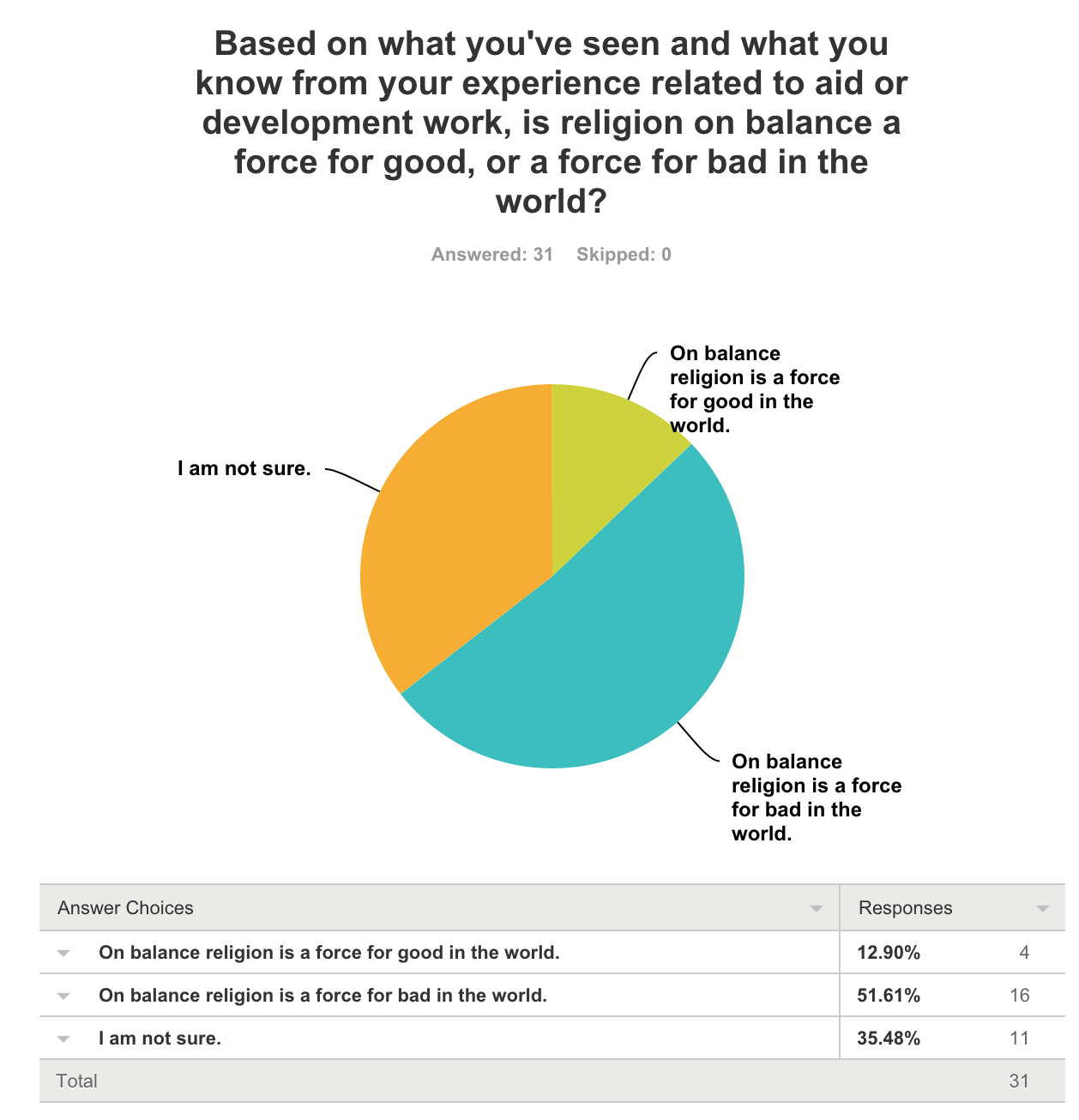

Is religion force for good in the world?

The specific question was “Based on what you’ve seen and what you know from your experience related to aid or development work, is religion on balance a force for good, or a force for bad in the world?” The vast majority of those who responded to this question indicated “I have an inside knowledge the aid, development, or charity sector/industry. I work or have worked for a charity or NGO, an institutional donor like DFID or the Gates Foundation, a beltway bandit like DAI, or I have been a consultant to one of these kinds of entities.”

The results, though clearly tentative, are dramatic. An anemic 13% of those responding felt that on balance religion was a force for good in the world. The rest were either not sure at 35% or, actually a majority at 52%, felt just the opposite.

Below are responses representing all three choices. I have highlighted what I think are particularly salient points.

First, on balance a force for bad. I have included two since this was the majority view, with the second representing a view evoking Marx:

- “To begin, I think that it is difficult to say on balance whether it is a force for good or bad, as many of the effects of religion are not necessarily quantifiable or equivalent, but considering the harm that is caused by religion, which cannot be negated by its good

impacts, I’m comfortable saying that it is a force for the worse in the world. Between the manipulation of religious beliefs to oppress, marginalize, and dehumanize people, often by religious authorities, and the conservative and reactionary character of many religious institutions, religion causes great harm around the world, especially when it comes to social justice. Being from the US, I’m very aware of how religious conservatism is a major driver of polarization and oppression in my country. That being said, I think there are many benefits of faith, and I know many people who are driven to good due to their faith or spirituality. From what I have experienced of the world, I think faith is seldom if ever an actual cause of things like oppression and conflict, but due to its fundamental and existential place in many people’s lives, it is susceptible to manipulation by people with power, especially those who have some form of religious authority. Faith and spirituality drive people to seek justice and make the world a better place, but religion can be used to exclude certain people from those deserving of sharing the betterment of the world. Finally, being an atheist, I find that many people still think having faith of some form is a prerequisite for being a moral person, and in many situations, not least at home in the US, I am not comfortable revealing my lack of faith. This I think gets at one of the greatest problems with religion, that it tends to prevent people from accepting without judgement others who are different from themselves, which is absolutely critical in the modern world if we are to successfully live together and achieve the aims of social justice and development that we strive for.”

impacts, I’m comfortable saying that it is a force for the worse in the world. Between the manipulation of religious beliefs to oppress, marginalize, and dehumanize people, often by religious authorities, and the conservative and reactionary character of many religious institutions, religion causes great harm around the world, especially when it comes to social justice. Being from the US, I’m very aware of how religious conservatism is a major driver of polarization and oppression in my country. That being said, I think there are many benefits of faith, and I know many people who are driven to good due to their faith or spirituality. From what I have experienced of the world, I think faith is seldom if ever an actual cause of things like oppression and conflict, but due to its fundamental and existential place in many people’s lives, it is susceptible to manipulation by people with power, especially those who have some form of religious authority. Faith and spirituality drive people to seek justice and make the world a better place, but religion can be used to exclude certain people from those deserving of sharing the betterment of the world. Finally, being an atheist, I find that many people still think having faith of some form is a prerequisite for being a moral person, and in many situations, not least at home in the US, I am not comfortable revealing my lack of faith. This I think gets at one of the greatest problems with religion, that it tends to prevent people from accepting without judgement others who are different from themselves, which is absolutely critical in the modern world if we are to successfully live together and achieve the aims of social justice and development that we strive for.”

- “Divisive regressive tool for social control.”

Next, on balance a force for good:

“The majority of people in the world are religious. The majority of people in the world live their lives peacefully (and are only unfortunately caught up in conflict if they are in a conflict area). Their faith brings them personal strength, and meaning as well as strengthening and organising communities. At the local level (which is ultimately the level aid should be concerned with), religion is a mostly a force for good.”

And finally, I am not sure:

“I see the strength and support it can give people, and a platform from which people perform generous acts, but I also see how it excludes, marginalizes, or encourages people (from many faiths) into more extreme posturing on issues of social justice and compassion.”

“I see the importance of faith + humility and understanding. No faiths can be proven and the religion I believe in is no more evidence based than another faith. I therefore cannot say or think that my faith is the correct one but it is just something that speaks to me in my heart and is very personal. I wish re ligious institutions would promote understanding and knowledge of different faiths. I wish they would not preach their way as being the only correct path. I wish they would also encourage enquiry and address the limitations of their histories and sources. Sierra Leone provides the perfect example of different faiths living harmoniously, ‘Jesus loves Allah’, ‘Allah loves Jesus’ written on cars.”

ligious institutions would promote understanding and knowledge of different faiths. I wish they would not preach their way as being the only correct path. I wish they would also encourage enquiry and address the limitations of their histories and sources. Sierra Leone provides the perfect example of different faiths living harmoniously, ‘Jesus loves Allah’, ‘Allah loves Jesus’ written on cars.”

To the respondent who wondered, ” Can we get away from these dichotomies? I will point out that though the question is certainly very complex, as is evidenced by other’s responses, pushing people to take a position on the question does generate useful dialogue.

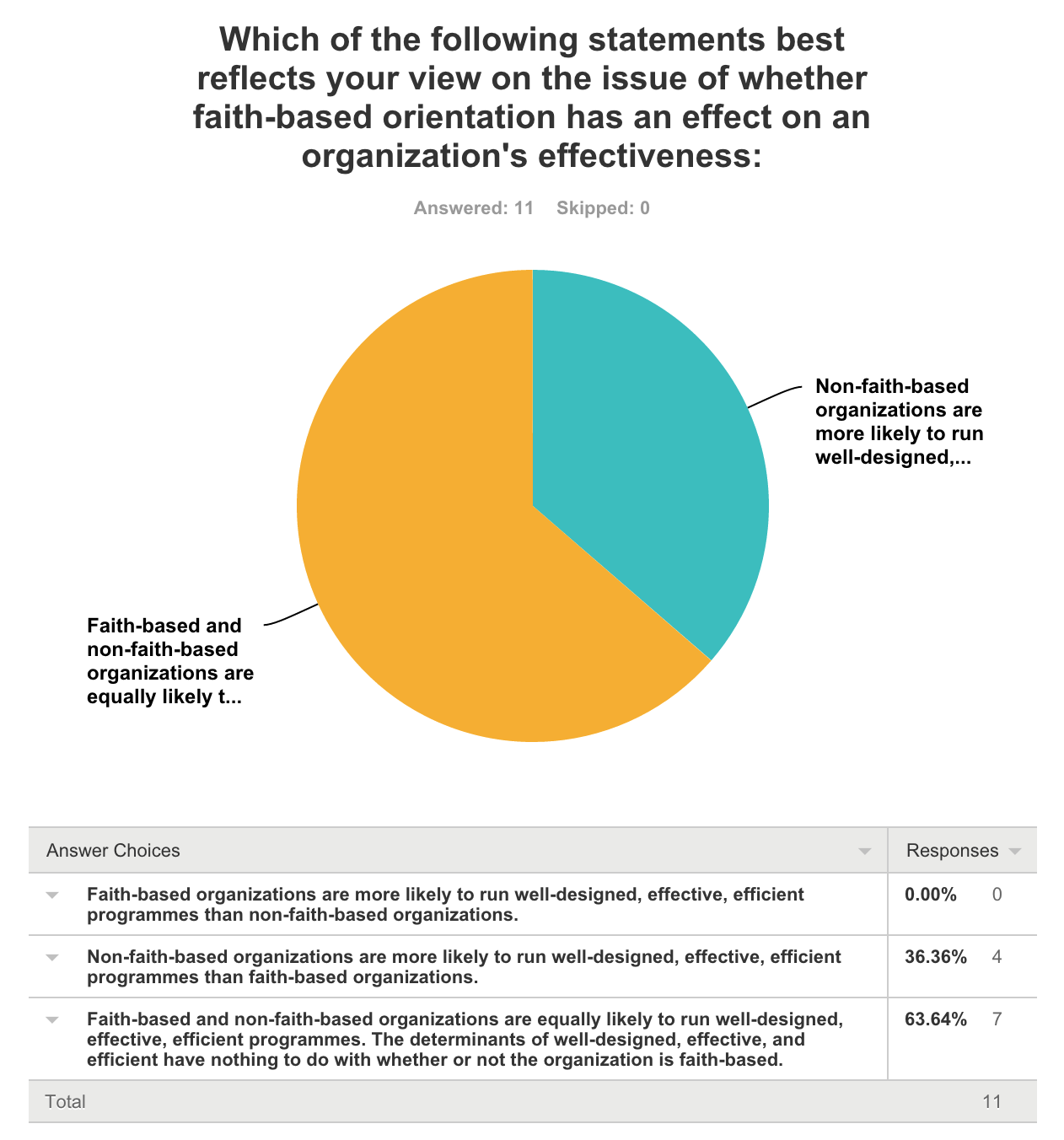

Faith based aid organizations ‘bad’?

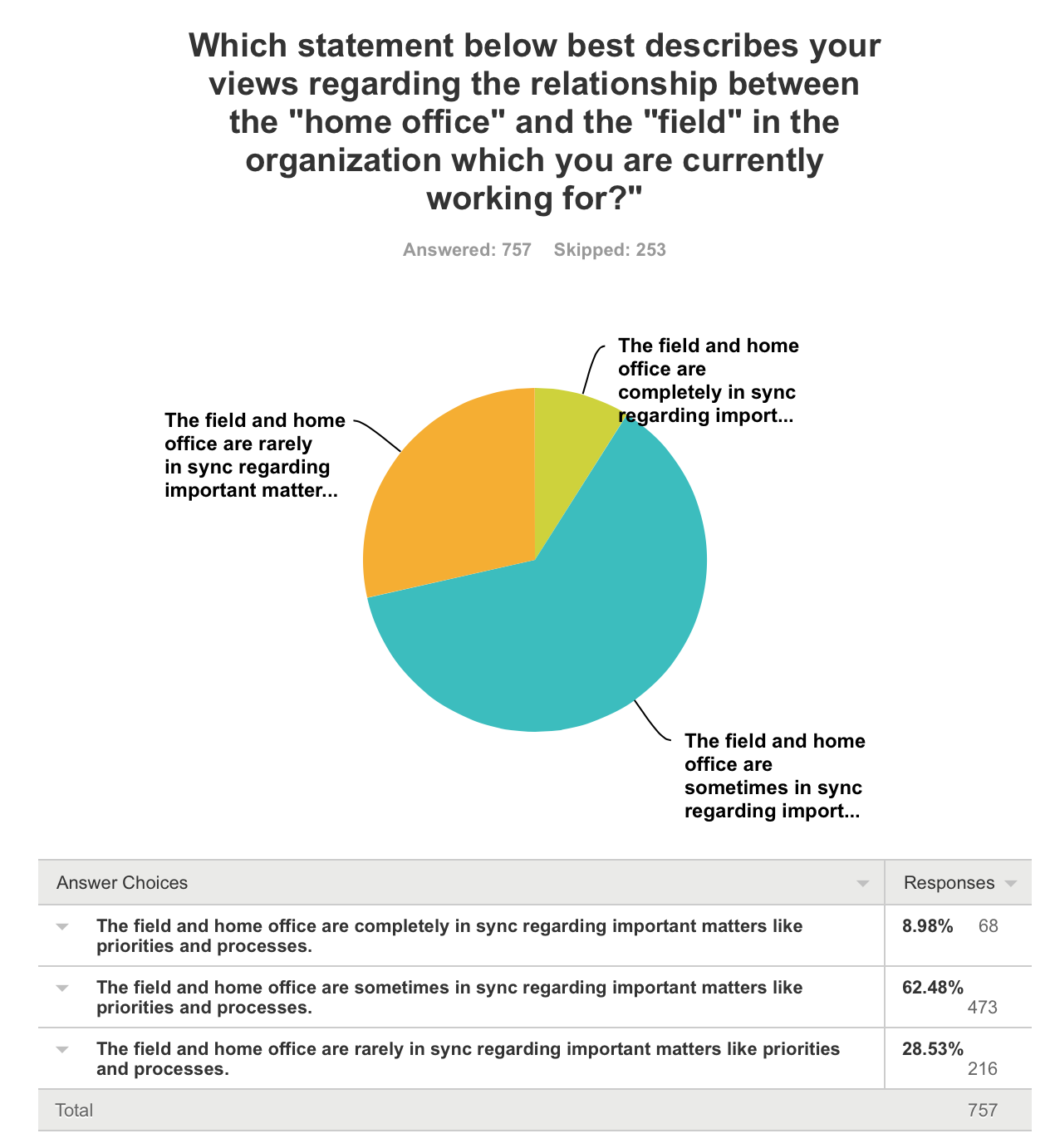

The next mini-poll generated some thoughtful responses as well. The key question was, “Irrespective of anything else, does the fact that an organization is faith-based or not faith-based have an effect on the quality, and ultimately the impact of its programmes and interventions in the field?” The results to this, 55% ‘No’ and 45% ‘Yes’, and what went behind these responses is hinted at in the followup question. Here are the quantitative results indicating the a majority of this small sample felt, of course, that it all depends, but minority opinion was biased toward non-faith-based organizations.

Here are a couple representative narrative responses that articulate some of the nuances.

“Truly, my answer is “depends.” I have seen both stellar examples of how FBNGOs leverage faith to the advantage of the population they serve and terrible examples how faith is used to excuse bad projects. Ultimately, the failures are due to bad management, which exists regardless of faith.”

“Depends on the context that the organisation is working in. If a faith based organisation is working in communities of the same faith then they can be more effective than others as they can engage deeper with people’s worldview and behaviour. However if working outside this context or in communities hat are not religious then their impact would not be different to non faith based organisations.”

Concluding thoughts

Religion is a major social force all over the world and has clearly shaped most of our past and clearly much of our present (see: ISIS). Understanding this force is critical for this who concern themselves with effective aid.

Let’s continue the conversation. EvilGenius has been busy as well so click here for an AidSpeak blog post on this topic.

As always, contact me with feedback on this or any post. The two most recent EvilGenius mini-polls linked above are directly relevant to the topic of this post. Again, if you have not done so already, please take the time to give us your thoughts.

Follow

Follow