Preliminary results from survey of aid and development workers in the Philippines

The gap

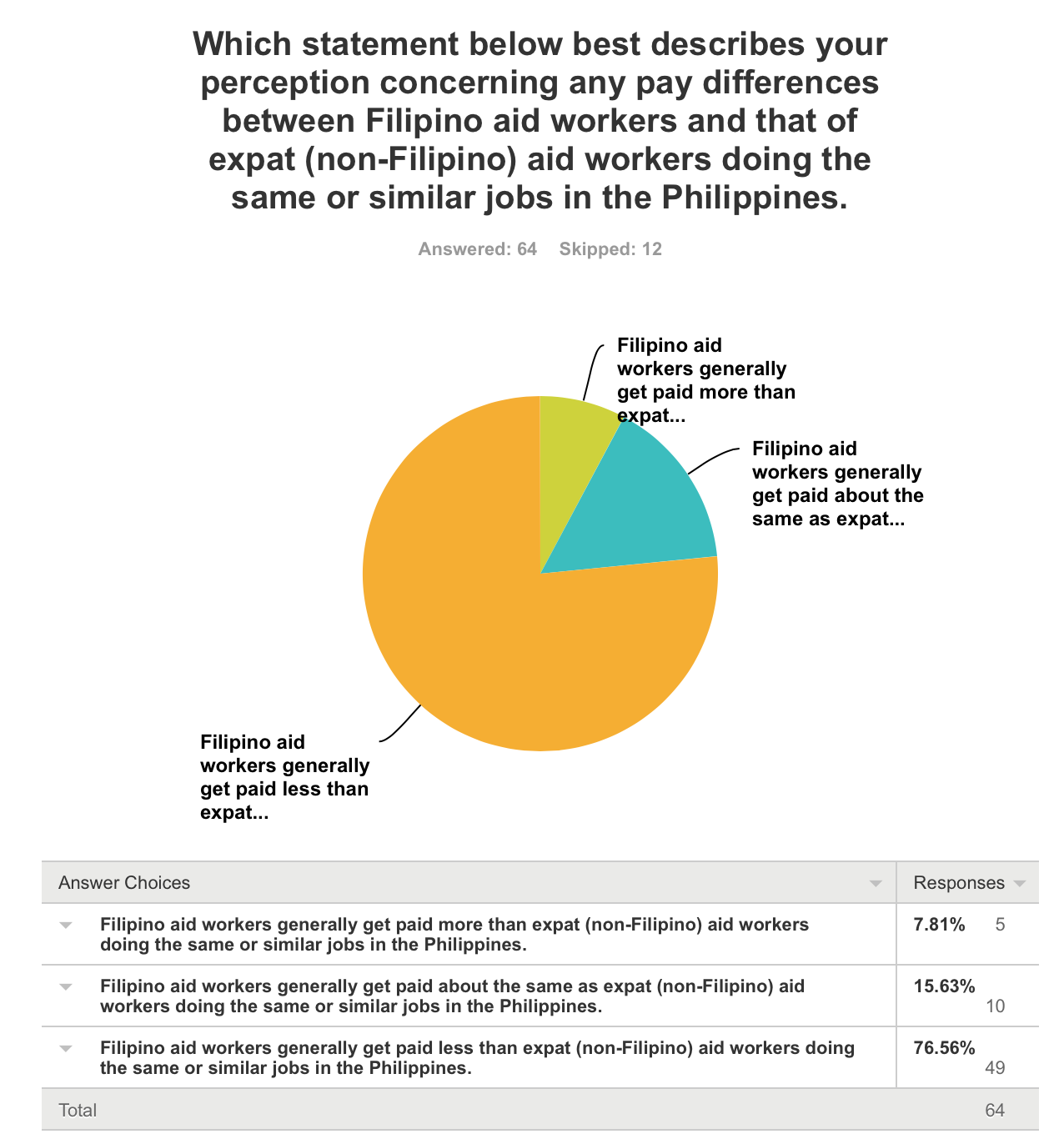

Among the questions addressed in our survey is the much discussed pay gap between local -in this case Filipino- aid workers and their expat counterparts. Other researchers have begun to drill down into this question, and the work teams based at Massey University/University of New Zealand (MU/UNZ) provide very useful data and insights specifically on the question “Are Development Discrepancies Undermining Performance?”

In a recent research note based on data generated by the MU/UNZ Project Add-up, Carr and McWha-Hermann said, “Expatriates are often quick to dismiss dual salary systems as a non-issue. But local workers told us a different story. They said disparities created significant feelings of workplace injustice. They felt less valued than their expatriate colleagues.”

Our current research in the Philippines is beginning to provide support for this statement. As you can see below, most -77%- agreed that “Filipino aid workers generally get paid less than expat (non-Filipino) aid workers doing the same or similar jobs in the Philippines.”

So far most of the comments about working with expat aid workers is that it is a “…very positive experience.” That said, there are some respondents who appear to feel acutely the differences between how locals and expats are treated regarding pay and other benefits.

So far most of the comments about working with expat aid workers is that it is a “…very positive experience.” That said, there are some respondents who appear to feel acutely the differences between how locals and expats are treated regarding pay and other benefits.

One respondent was very pointed,

“Mostly, expats get paid like 10x higher than the local workers and enjoy all the benefits like free board and lodging, higher per diem when doing field work, and they can demand good and high class hotels for accommodation, but for the local they need to justify all this to enjoy these benefits. In terms of risk and security, during field work if it like dangerous, it is okay for expats not to go to the area, but for locals it a must to deliver your expected result even you are doing same job. Expats can hire good vehicle or they are provided of good transportation when sometimes locals should take the local transportation.”

The relationship

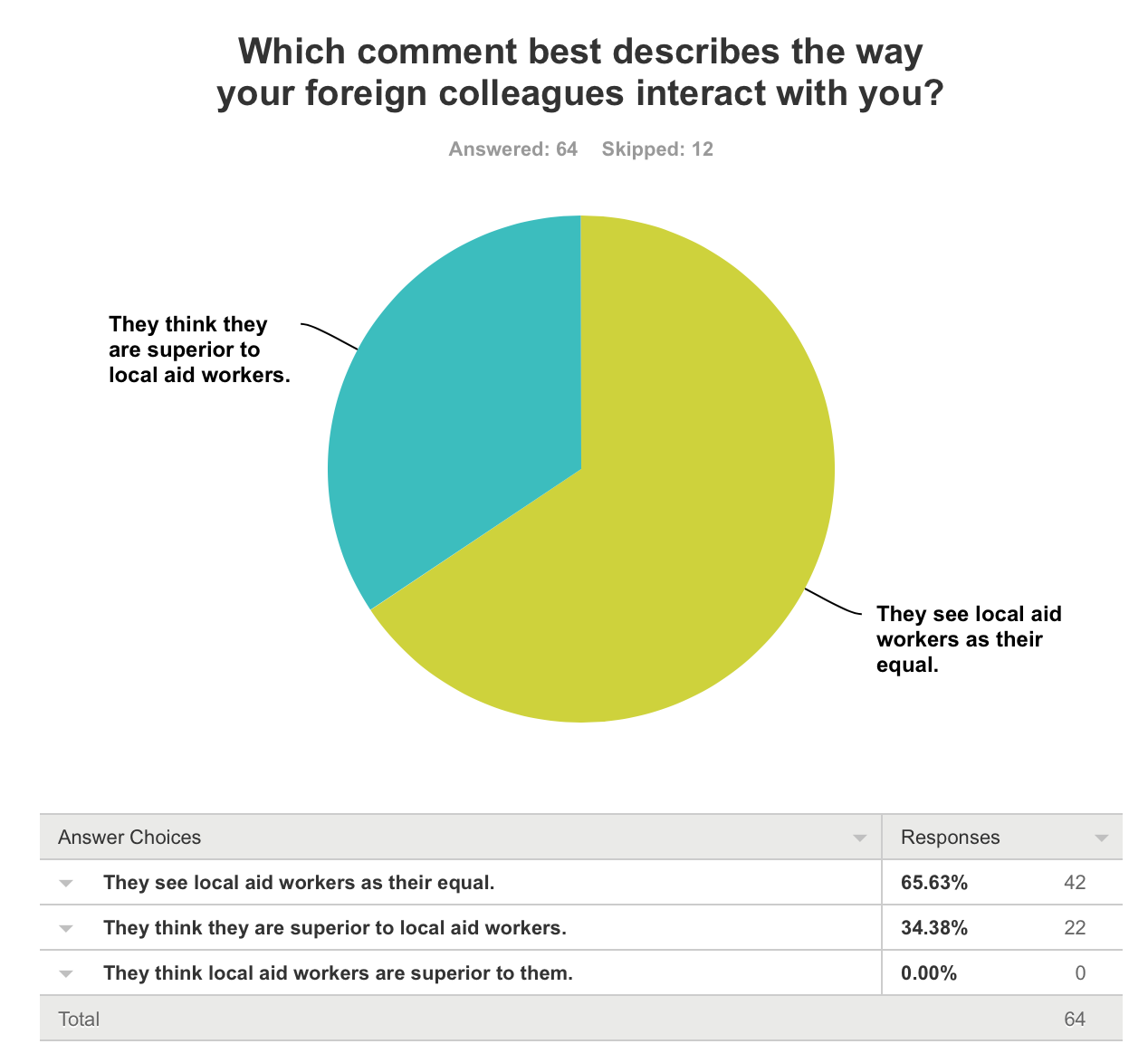

How do Filipino aid workers feel about working with expats? Over 84% indicated that “I generally have a positive working experience with foreign colleagues.”

They are generally happy dealing with non-Filipinos because, in the words of one respondent,

“Working with non Filipino colleagues is a great experience in my life because we share our ideas freely and we gain more knowledge from them and they are kind to us.”

I am troubled by the last phrase “… they are kind to us.” Another said,

“Its a great previllege working on them … such an honor.”

Again, I am troubled by the language being used here and sense a pattern indicating a distinctly asymmetrical power dynamic. This survey question “Which comment best describes the way your foreign colleagues interact with you? gets to my point, perhaps.

As you can see to the right, well over a third so far feel that [foreign colleagues] think they are superior to local aid workers.

We have no specific data as to the research question cited above (“Are Development Discrepancies Undermining Performance?”), but my sociological instincts lead me to suspect at least a slight impact on performance.

As more data come in there will be more posts and comments. The survey will remain live for the next few weeks giving the chance for more Filipino aid and development workers to have their voices heard. In the meantime my collaborator, Filipino aid worker Arbie Baguios, and I will continue reviewing the data looking for patterns and notable quantitative results.

An additional thought on the gap

The question, “Is the wage gap between expats and locals a function of the market – or plain old discrimination? is certainly worth asking, but the answer will, I hazard, more complicated than a yes or no. All organizations -both inside the aid sector and well beyond- struggle to determine what is fair in terms of compensation packages and then finding a way to balance doing what is fair and doing what is practical, and that may mean cutting overhead by minimizing ‘local’ wages based on the blind logic of the market. The driving logic may be that the money saved, after all, can be used to provide more aid. And, yes, some might argue, this is ‘plain old discrimination.’

So, to conclude on an anti-neoliberal note, a truly just world will never happen as long as we allow an acephalous, amoral (and, hence, immoral?) system to determine how most decisions are made.

Comments or feedback? Reach me here and Arbie on Twitter @arbiebaguios.

Follow

Follow