Hi! My name is Zoë Rein and I’m a junior majoring in English with Teacher Licensure and Math with a minor in TESOL. Outside of The Writing Center, I’m an Honors Fellow doing research on writing and a director of Alternative Breaks! What is the last thing I feel like doing after writing my first draft?

What is the last thing I feel like doing after writing my first draft?

Writing the next one.

Going through the process of reading confusingly organized paragraphs, half-formulated ideas, and repetitive sentence structures is uncomfortable and painful. Sometimes, I think to myself that the first draft is “good enough,” and I can turn it in as is. Especially during those late nights or last-minute moments where The Writing Center and my friends are all asleep, it becomes easier to turn away and condemn the paper to its unrevised stage.

Yet, that early draft stage won’t pack as much of a punch as a well-organized, thought-out, and properly designed paper. Writing has the potential to change opinions, teach new ideas, and inspire creativity (as well as potentially get an A); but this doesn’t happen with just a quick glance at spell-check.

What does it mean to revise?

While many professors remind us to revise, I’ve learned that my definition of revision is, in fact, contrary to its actual meaning. I always thought of revision as just another look at my draft. Grammar concerns, spell-check, and word choice dominate my to-do list. If I’m in a time crunch, this feels like as much revision as I can handle.

However, this is proofreading, not revision.

Proofreading encompasses those last steps before you reach a final (for now!) draft, such as spelling, grammar, and punctuation. On the other hand, Walden University’s Writing Center, along with lots of other writing experts, remind us that revision is a more overarching process that re-analyzes a paper’s ideas and structures. It’s all about the BIG PICTURE!

Ideally, revision takes time and thought in order to focus on grand scheme ideas and elements of the writing. This is precisely why true revision terrifies writers like me. Revision requires vulnerable re-evaluation of thoughts that I already put effort into, so this stage necessitates deep engagement with words I love or hate. With the next draft, or drafts, I may add, cut, or rethink, making the journey to a final product an emotion-ridden roller coaster.

However, good intentions aside, I frequently find myself rushing to finish projects by trying to combine the writing stage with the revision stage. “Editing as I go” is a supposed time-saver, but it actually stunts the full extent of the process. Writing researchers Flower et al. distinguished amateur versus advanced writers because the experienced group spent the time to create a revision plan after the completion of a first draft (18).

In a world with no other obligations, a writer could spend weeks revising. However, we can still produce an impactful plan by choosing strategies that best fit the needs of our drafts. While it might be enticing to put down my laptop or let autocorrect do the work, I’ve found a couple of meaningful revisions can elevate a paper from first draft to final product in just a couple of hours.

Tip 1: Set your agenda

As Flower et al. found, agenda setting is crucial to understanding your individual revision process. Similarly, UNC Chapel Hill’s Writing Center suggests that each unique paper demands a unique next step. While these tips apply to common concerns, only you know your paper’s needs.

First, think honestly about your timeline. What prevents you from focusing on the paper? How much time can you and do you want to commit? In this timeline, how much can you accomplish?

From here, I suggest choosing three feasible areas to focus on. Select areas that would benefit from an extra 30 minutes, not just the sections that feel easiest to tackle. For instance, maybe you have a solid introduction, but the conclusion ends on a low note. The conclusion will gain more from the added attention even if addressing the introduction first feels more intuitive.

Try writing your essential three items followed by three additional possible areas if you have the time to focus on more of your paper. I like to write each task on a Sticky Note so I feel the satisfaction of crossing out completed tasks. I also make sure not to guilt myself if all I finish are those three essential tasks. This step is all about prioritizing, and sometimes that means not finishing everything perfectly!

Tip 2: Read aloud to re-hear

UNC’s Writing Center reminds us that to revise literally “means to ‘see again.’” However, equally useful is the opportunity to hear again! Reading out loud changes your perspective of the material you’ve thus far only seen on paper. One of the first things an Elon Writing Consultant (but also at Walden or UNC) will often ask you to do is to read your paper aloud.

While you’re reading, mark notes about what you think needs work. Listen carefully for organization in and between paragraphs. Does this paragraph completely diverge from the ones before and after? Does the sentence logically continue the argument?

Starting with this strategy also helps set your agenda. Whenever listening to a section makes me cringe, I know it needs to be in my to-do list.

Tip 3: Check your evidence and support

Evidence and supporting analysis will build the bulk of your paper. After all, most types of writing, whether lab report or literary essay, ask you to defend a big claim – your thesis – and several smaller, supporting ones. A professor once told me, “Don’t be a liar! Defend your thesis!” which UNC’s writing center rephrases as keeping true to your thesis with on-track and supported claims.

We can check that the paper follows through on the claims it makes as well as incorporates the appropriate evidence and analysis to make a balanced paper. UNC suggests keeping track of which points you emphasize or ignore. Although some points may naturally stand out more, try to equally weigh the paper (UNC).

Here are two strategies to check your evidence:

1. Reverse Outline

While reading through your paper, mark the margins up with the evidence and analysis you included for each paragraph. By the end, you’ll visually see which paragraphs have more or less support. You can use reverse outlining for many revision elements, so as you mark evidence feel free to add in notes about overall paragraph topics.

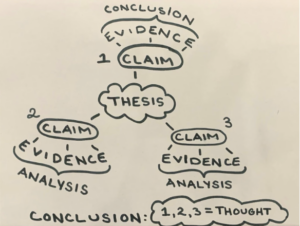

2. Mind Map

A mind map asks the writer to start with their thesis and then visually represent how their claims, evidence, and analysis fit together. After creating the map, you should see what points you use to back-up the thesis statement. Thus, you find if the points mesh with each other and the thesis. This strategy is especially useful if you like visual representations of your paper and find yourself struggling to picture how each element of your writing connects. Tip 4: Topic sentences

Tip 4: Topic sentences

My final tip is for inner-paragraph cohesion. This is a great step when you feel as though you incorporated solid evidence and analysis. Although reverse outlining or mind mapping promotes organization between paragraphs, you also must make sure the content in a paragraph aligns. One of my fatal mistakes while writing is creating an extra long paragraph that encompasses five loosely connected points. It’s almost impossible to remember the topic sentence’s argument by the time I finish!

I like to think of the topic sentence as the paragraph’s guide. Like the thesis statement, topic sentences usually make a claim or argument, and it’s the paragraph’s job to defend that all the way to the last sentence (see tip 3!). I like to quickly check for unity by first reading only the topic sentence and the concluding sentence. If the two make sense together, I know my paragraph is mostly on track.

Another more thorough strategy is reading every sentence and checking that it aligns with the first one in the paragraph. If you find that the paragraph splits into two directions, make them separate paragraphs! If you appropriately support your points, the number of paragraphs is not typically a concern. Breaking them apart may also help you find holes that you can elaborate on! If you feel like the paragraph shouldn’t be broken up, keep returning to the topic sentence until its argument is broad enough to sustain both sections of thought. And sometimes the topic sentence is the only one that’s different from the rest of the paragraph, and then you know that you just need to rewrite that first sentence.

Give it your all!

Revision can be a confusing and, frankly, frustrating process. However, devoting even one or two hours to your revision agenda will take your paper to a whole new level! Set a timer, find your writing mojo, and use these tips to make your work shine!

Cailey Rogers is a class of 2024 Writing Center consultant. She is studying Journalism and English Literature. At Elon, she is a Communications Fellow and is involved in Elon Learning Assistance, Colonnades Literary and Art Journal, and the Pendulum.

In my short time at Elon, I have found that the most challenging and rewarding part of writing a long literary analysis paper is the thesis statement. It’s funny how just one small portion of what can become an eight-page essay seems impossible to accomplish. If you feel that way, you are certainly not alone. Even English majors struggle with it – I can say that from personal experience! That is exactly why I decided to share the tips and processes that have helped me the most when writing a literary analysis thesis statement in hopes that it could help others staring at a blank document, not knowing where to start or feeling like they will never be able to write a good paper about a piece of literature. If you want to know some of the general tips and tricks that I have acquired through my English classes and some other resources, you can read my first blog post here.

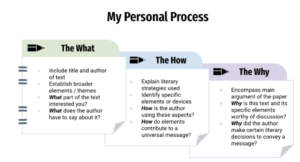

The What, The How, and The Why of a Thesis Statement

For my personal process, I approach writing a thesis statement like writing a puzzle with three different pieces that fit perfectly together. I call these pieces the “what,” the “how,” and the “why.” Sometimes, this means that my thesis statement consists of three different sentences, each fulfilling one purpose; sometimes I can check off two or more of the pieces in just one sentence. But don’t feel the need to limit yourself to one single sentence when you’re writing a thesis statement. I’m here to tell you that the “one sentence thesis statement” rule that was enforced in middle school and high school was made to be broken. Literature is inherently complex, so it is natural for your literary analysis essays to be equally intricate. Take an extra sentence or two; it certainly couldn’t hurt. I try not to go beyond three, though, because then you are writing an introductory paragraph. Just make sure to check off these three components first and worry about streamlining later.

To illustrate this process, I will now break down each of the three pieces and use a thesis statement I used for my literary analysis on Frankenstein by Mary Shelley as an example.

The What:

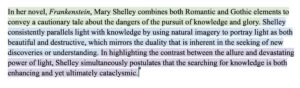

The first part of my thesis will state something about the text that I know I want to focus on, or that contributes to my argument. This can be a significant pattern, something important about the time period the text was written in, or a larger theme that I want to delve into. This sentence is also where I would include basic information about the title of the text and its author. For example, my first sentence of my Frankenstein thesis statement reads:

The first thing the sentence does is establish the text and author, but what follows is a very straightforward statement that establishes both the types of elements the essay will focus on (Romantic and Gothic), and what the author used them for (to tell a cautionary tale about the dangers of pursuing knowledge). So really, the purpose of this one sentence is to tell the audience the broader topics that will be discussed before delving into the specifics of the analysis. It doesn’t just introduce what aspects of the text I will be focusing on, but also what the author did with them. Think of this part as a preview to the rest of your thesis and the paper as a whole. Use this as an opportunity to show what part of the text really interests you, and in the next two parts you can go into what you have to say about it.

The How:

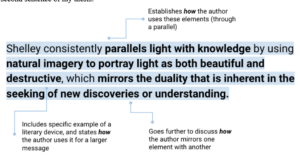

The second piece of the puzzle usually consists of explaining what literary strategies the authors used in order to develop a theme, highlight certain elements, create a pattern, etc. This is where you can start to identify some more specific ideas or elements that you will discuss throughout your paper, while also showing how those facets added to a more universal message (remember the idea of addressing the wider implications of the text from my first blog post). Here is the second sentence of my thesis:

While in the previous sentence I say what Mary Shelley used Romantic and Gothic elements for, in this statement I not only say which specific elements those are, but also how she uses them to convey a larger message. Instead of letting the statement remain broad, I explicitly outline that I will be analyzing light imagery. Then, I go further to discuss how Shelley used light imagery as parallel to knowledge, and therefore highlighted a sense of duality in both elements. This starts building a clear roadmap for your audience, as it now becomes evident that my essay will provide examples of light being mirrored with knowledge and highlight the dual natures in each of them. You want your thesis to be able to stand alone, so this sentence becomes crucial to introducing specific details of your paper, but also giving your reader an understanding of how you will be engaging in an analysis with those elements.

The Why:

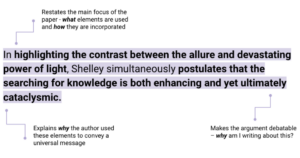

To me, the final piece is the most important, because it should encompass the main argument that you will be defending in your analysis. It should not just state why the author made certain decisions to portray a message – as in, what point was the author trying to make when including certain themes, patterns, or literary elements – but it should also make it clear why you are writing about it. This should be the crux of your analysis, and it should also be the part that is really debatable about the thesis. Make sure to include your own ideas: What are you arguing about this text and the literary choices embedded within it? What does this analysis say about the overarching aim of the text itself? This was mine:

Finally, I state the key piece of the argument and analysis that drives the whole paper. I make sure to include the specific literary elements that I summarized in the previous sentence (the duality of light and knowledge), but I now explain why I think Shelley included them and what universal message she wanted to convey through that aspect of her novel. By laying out the author’s reasons behind certain literary choices, I simultaneously elucidate the purpose behind my analysis as well. It becomes evident that I want to prove that one of Shelley’s aims in writing Frankenstein was to illuminate the danger of knowledge – this wraps up the thesis perfectly because it finally makes it truly arguable. Anybody could have pointed out that Shelley included light imagery in her novel, or even that she highlighted the duality of knowledge throughout the text. But this sentence makes my thesis more individualized because I now argue why she does that.

If you can get this part of the thesis right, you are more than halfway there. To test if this vital part is working, try isolating it from the other two pieces – if it works on its own and makes your argument comprehensible to your audience, then you’re certainly on the right track.

The full thesis statement ends up like this:

If you ever find yourself struggling with a literary analysis thesis statement, please come and run it by one of the writing consultants at The Writing Center! We’d be happy to help you in anything you need, but if you are writing a literary analysis essay, you can always find me. As I said, they are my favorite things to write, and I would love to help you with yours!

Cailey Rogers is a class of 2024 Writing Center consultant. She is studying Journalism and English Literature. At Elon, she is a Communications Fellow and is involved in Elon Learning Assistance, Colonnades Literary and Art Journal, and the Pendulum.

I distinctly remember that when I was in middle school and just beginning to learn how to write essays, the most daunting task was crafting a thesis statement. Back then, my teachers would put so much emphasis on one part of the entire paper; now that I’m in college, I understand why.

Writing a thesis statement hasn’t become easier over time for me. In fact, now that I am writing complex papers for my 3000-level classes, it has proved to be even more challenging. But honestly, I have come to appreciate this part of a paper to the point where I cannot write the body paragraphs of my work until I am satisfied with the thesis statement.

As an English Literature major, I most look forward to writing thesis statements for literary analysis essays. But I realize that the idea of writing a long analysis on a piece of literature is not fun for everyone. Well, I’m going to offer some suggestions and advice to anyone tackling a literary analysis paper – whether this is your first time writing one, or you’ve been doing it for years, these thesis statement tips will give you a roadmap to creating a thesis that will not just start your paper off on the right note, but also display your writing skills and critical thinking. If you have a strong thesis, I guarantee that your paper will be more sophisticated and easier to write. While my focus here in on literary analysis, my tips apply to anyone writing an analysis and interpretation of a text.

Like any thesis statement, a literary analysis thesis should work as both a roadmap and a foundation for your essay. As the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill advises, the thesis statement should do more than illuminate how you are going to “interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion;” it should also give the reader an outline of the paper itself. This means you need to state what topic you want to focus on, what specific details you will use as textual evidence, and why your argument is important. If you draw a clear map and build a sturdy foundation, the rest of your analysis can grow to be much stronger as a whole.

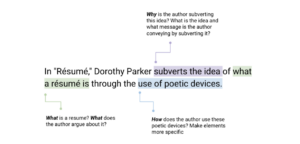

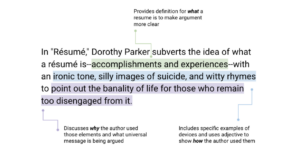

Let’s break down an example that may make this point a little easier to digest. Here is a practice thesis statement from the WAC Clearinghouse that distinguishes between a vague thesis and one that provides a detailed blueprint for the paper:

Original:

Revised:

In the first example, the thesis only mentions that the author uses poetic devices, but the second one lists out each of the specific devices that the writer will focus on: tone, imagery, and rhyme. It would then be expected that the essay would follow a specific structure that expands on each of those devices following the same order. Also, the second one adds an extra bit of nuance at the very end to show what the author is using those elements for and what larger argument you will connect each piece of evidence to. The second thesis is not only more developed, but it also provides a clear outline for the paper itself.

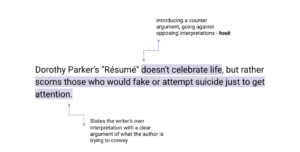

Another valuable piece of advice is to make sure not to state the obvious in your thesis statements. In addition to thinking of your thesis statement as a map or a foundation, think of it also as a hook. You want your readers to be interested in what you have to say, so make your thesis statement compelling enough so that a reader simply can’t resist reading the rest of the paper.

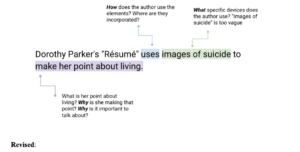

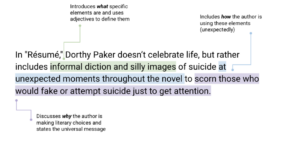

Here is another example from the WAC Clearinghouse on how to accomplish this feat:

Original:

Revised:

While the first statement seems quite straightforward and incontestable, the second one adds the writer’s interpretation of the text and implies that they are going to be arguing against an idea that this text “celebrates life.” I would expand this thesis even further by adding more specific examples and details of the analysis. This sentence clearly states an interesting argument, but there is certainly more the writer could expand on to enhance the quality of the thesis. Here is what I would add:

While the first statement seems quite straightforward and incontestable, the second one adds the writer’s interpretation of the text and implies that they are going to be arguing against an idea that this text “celebrates life.” I would expand this thesis even further by adding more specific examples and details of the analysis. This sentence clearly states an interesting argument, but there is certainly more the writer could expand on to enhance the quality of the thesis. Here is what I would add:

Expanded:

Note: To learn more about the “what,” “how,” and “why” aspects highlighted in these examples, check out the second blog post in this series, where I discuss my own personal process when writing a literary analysis thesis statement here!

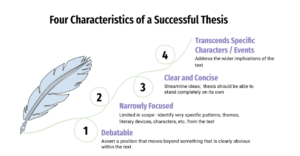

Now, these may seem like pretty standard suggestions that would work for all kinds of thesis statements across a variety of fields. And they are. That doesn’t mean they aren’t important to keep in mind, though. But I did come prepared with some suggestions that are specific to writing a literary analysis essay that I have learned from Dr. Janet Myers, Professor of English in the English Department at Elon University. I’ve taken several classes with Dr. Myers, written countless literary analysis papers, and these four simple characteristics to include in a thesis statement have gotten me through each one. According to Dr. Myers, these are the four characteristics of a successful thesis statement:

By this, I mean that you want to assert a position that moves beyond something that is clearly obvious within the text. More specifically, you are going to want to isolate a subject you can explore with your own voice. You don’t want to merely point out that a theme of pattern exists in a text; you want to argue about its meaning or purpose. Think of everything you write as being a contribution to a big conversation of scholars. What do you want to contribute to this conversation? You don’t want it to be just an observation but rather an argument that you can support and defend.

2. Narrowly Focused

Even though you do want to address some universal and pervading aspects of the text you are analyzing, you definitely don’t want to overburden yourself. The broader your thesis is, the more you would be required to explain, and the harder it would be for your audience to understand the particulars of your argument. So, make your thesis statement limited in scope. Identify a specific pattern, theme, literary device, character, or historical event (and there are certainly more possibilities) from the text that you want to analyze in your paper. This is where you could build the roadmap aspect of the thesis: list the elements in the order you will write about them in, and suddenly you will have a clear path for entire literary analysis.

3. Clear and Concise

This may seem obvious, but it is crucial. A clear thesis will play into the idea of a roadmap, but it will also avoid using long, complex clauses or unnecessary jargon. In terms of making it concise, look for any words in your thesis that may not add to the overall point you are trying to make, and cut them out. Streamline your thesis statement by simplifying your ideas as much as you can, almost as if you were trying to explain it to someone who has never read the text before. Ultimately, your thesis should be able to stand completely on its own. If you just gave your professor your thesis statement and left out the rest of your paper, your topic, evidence, and argument should all be transparent and evident.

4. Capable of Transcending Specific Characters and Events in the Text

This one is particularly important to keep in mind for a literary analysis paper. What makes a strong literary analysis is an argument that isn’t limited to one specific plot point or character within the text. Think of it this way: pretend you are trying to convince a friend that they should take up reading as a hobby because it is entertaining and enriching. But the only evidence you have to back this up is that you really enjoyed reading one book in the past month. Obviously, that is never going to convince your friend to take up reading because that argument only pertains to one person’s experience at a singular point in time. You would want to have more examples of how reading has changed people’s lives across the world, not just you. Also, you would probably want to address some of the larger persuasive arguments like how literature increases the value of an education, or how it can teach you about a variety of different topics. You would do the same thing in a literary analysis paper: you would want to address the wider implications of the text and find patterns or themes that pertain to more than one specific event or character. Challenge yourself to find connections between events and characters, and then trace those connections in your writing. But even more than that, try to find a universally significant message that your text represents. Literature is a reflection of reality, so find out what your text is trying to express about the real world, and then write about it.

I know it can seem intimidating to write a literary analysis paper, but if you follow these tips when writing your thesis, the challenge will suddenly seem much less impossible. If you want to continue learning about writing a successful literary analysis thesis statement, you can find another blog post I wrote about my personal process and tips by clicking on this link. And if you still find yourself doubting your work, you can always come to The Writing Center, and we would be happy to help you!

Hi, I’m Sofie Campbell. I’m a member of the class of 2024, double majoring in Marketing and English Literature and minoring in Professional Writing and Rhetoric. I also work as a Writing Center Consultant.  There comes a time in every writer’s life when they must do the unthinkable: allow someone else to read their writing. It happens to the best of us, myself included. Sharing your writing for the very first time can be an intimidating prospect, especially when first entering college. It can sometimes be an uncomfortable experience, especially if you’re prone to writer’s anxiety.

There comes a time in every writer’s life when they must do the unthinkable: allow someone else to read their writing. It happens to the best of us, myself included. Sharing your writing for the very first time can be an intimidating prospect, especially when first entering college. It can sometimes be an uncomfortable experience, especially if you’re prone to writer’s anxiety.

What’s writer’s anxiety? Here’s some common scenarios:

- “I sit down but then choke.”

- “I paralyze myself by overthinking.”

- “I feel completely unprepared.”

- “I’m terrified that my ideas won’t be good enough.”

If you’ve ever experienced one of these thoughts before writing or during writing, it may have been writer’s anxiety. This can lead to writer’s block–and trust me when I say you’re not alone here. Writer’s anxiety is when a person experiences “negative, anxious feelings (about oneself as a writer, one’s writing situation, or one’s writing task) that disrupt some part of the writing process.”

What causes writer’s anxiety? Here’s a few examples provided by the UC Berkeley Writing Center:

- Fear that criticism of an essay is the same as criticism of a person’s self-wort

- Fear from past bad memories and negative experiences with academic writing

- Conflicting information on how to write

- The pressure of feeling the first draft must be perfect

- The misconception that every word must be edited as you work on a first draft

- Fear of writing an essay that is less than “perfect”

Sometimes a writer deals with their writer’s anxiety internally, so it’s important to ask ourselves questions that help us gain control of our anxiety. Asking yourself the following questions and answering them honestly is the first step to acknowledging and then dealing with writing anxiety.

- What are my expectations for myself?

- What are the professor’s expectations of me?

- How can I better balance my class schedule?

- Is my anxiety a one-time occurrence or a common situation for me?

- How do my lifestyle choices affect my academics—am I doing something too much or too little?

While it’s important to acknowledge our anxiety, there’s also some specific strategies that we can use to make writing easier when we might feel overwhelmed or anxious. Some suggestions from the University of Richmond Writing Center include:

- Break up the paper into segments based on the specific areas or arguments the paper will explore. Then, work on one piece at a time. Try an outline to help create these segments.

- Set goals, such as writing section “A” on Monday, and then take a reward. Breaks and small rewards (buying a soda, calling a friend, watching a favorite television program, etc.) keep one’s mind from getting fatigued, and they reinforce positive behavior.

- Resist the urge to edit as while writing. This interrupts any thought flow, and it often wastes time in the long run. Focus on getting out the ideas first. The writer can stop and review later.

Finally, meeting with a Writing Consultant at Elon’s Writing Center can help you manage the writing process, feel less isolated, and of course help make the paper more clear and coherent. Click here to review consultant availability.

Hi! My name is Caroline Murphy and I’m an English major with a concentration in education with a minor in TESOL. I’m a member of class of 2024 and work as a consultant in the Writing Center.

There’s a lot to consider when beginning the process of writing, whether you’re writing for an assignment or your own enjoyment. When starting to write, one question that’s important to ask yourself is: “Who am I writing for?” The person or group of people you expect to read your work, and therefore who you’re writing for, is your audience. In this blog, I’ll be discussing some helpful tips for how you can consciously consider your audience while writing.

The easiest audience to identify is yourself. Whether you’re journaling, making a to-do list, or doing other personal writing, you’re your own audience. However, if you’re writing for another person or group of people, you need to identify them. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center has compiled a list of questions to ask yourself when beginning to write:

● Who’s your audience?

● Do you have more than one audience? If so, how many audiences do you have?

● Does your assignment itself give any clues about your audience?

● What does your audience need? What do they want? What do they value?

● What are they least likely to care about?

● What do you want your audience to think, learn, or assume about you? What impression do you want your writing or your research to convey?

Your tone, diction, style, and overall themes could be affected by your audience, whether you are writing an assignment for a professor, completing an application for a study abroad program, crafting a social media post, or writing a short story or poem. Keep in mind your audience could also change the content of your piece.

As you consider the questions above while writing, you may feel more inclined to cut out certain things that you normally would include, or include things you typically would not write. For example, the professor for your literary analysis class is asking you to write about symbolism in Jane Eyre. You might want to include more connections to specific scenes and dialogue that supports your argument, opposed to having more plot summary. Wanting to leave your audience with a lasting impression may encourage you to improve your overall writing quality.

What should you do when your audience is your professor? UNC’s Writing Center says that even if you’re writing an academic paper, it’s effective to tailor it toward a broader audience than just your professor. They obviously know about the assigned topic; however, by imagining them as the sole audience, it’s easy to write about ideas without expanding on them. This may cause the professor to assume that you don’t have a clear understanding of the topic. So, treat your professor as an “intelligent but uninformed” audience member, and provide the same context and explanation that someone not in your course would need to understand your paper’s central ideas. (UNC Chapel Hill’s Writing Center).

A final tip is to consider yourself as a member of the audience as you read your drafts. This will help you remain unattached as you reread your work and see things you usually gloss over as the writer. If you need assistance during any stage of the writing process, book an appointment with Elon’s Writing Center!

Hi, I’m Ellie Banfield, a class of 2024 Writing Consultant. I’m majoring in English Literature, and I have experience with blogging, creative writing, and professional writing.

Have you ever been told to change your writing from passive to active? I know I have, and I also know this can be a frustrating comment to receive if you aren’t sure what the difference is between passive and active voice. If you can relate to this, then you’ve come to the right place. This post will discuss the differences between active and passive voice, and help you avoid confusion in your own writing.

Let’s start by making sure we’re clear on what passive and active voice is. In a passive sentence, the subject is acted upon by the verb. For example: Your glasses were broken. We don’t know how the glasses were broken or who broke them, but we do know it’s not possible for glasses to break themselves–resulting in a passive sentence. To change this example sentence to an active one, we need to add a subject to act on our verb. So, the sentence could be modified to: I broke your glasses. As the younger sister I am, I like to think about active voice as assigning blame to someone or something.

It’s important to note that passive voice isn’t always bad. In fact, it’s encouraged throughout scientific genres and composition. Here’s an example of passive voice for a scientific report: “Samples were collected from six counties by our research team.” It’s not necessary here to put the subject first because it doesn’t matter who collected the samples; it only matters if they were collected.

Sometimes, passive voice is the better option. Purdue Owl says, “passive voice makes sense when the agent performing the action is obvious, unimportant, or unknown or when a writer wishes to postpone mentioning the agent until the last part of the sentence or to avoid mentioning the agent at all.” Purdue Owl explains two occasions when passive voice can be the better option:

Active:

The dispatcher is notifying police that three prisoners have escaped.

Passive:

Police are being notified that three prisoners have escaped.

In this scenario, the passive sentence is the better option. It’s not necessary to know who’s notifying the police; it only matters they’ve been notified.

One downfall of passive writing is that the sentence can get complicated. As Porter says, with passive writing “ the writer is forced to construct longer sentences than might be required by the active voice. An opportunity is thus created for the introduction of obscure, pompous words and convoluted phraseology.” There’s specific circumstances when you need to use an active voice. To change from passive to active, “consider carefully who or what is performing the action expressed in the verb. Make that agent the subject of the sentence, and change the verb accordingly.”

I hope you have a better understanding of the difference between passive and active voice, and when it’s appropriate to use both. If your professor or a classmate tells you to work on your passive/active voice, come see me or one of my colleagues in the Writing Center.

Hi, my name is Avery and I’m a class of 2024 Writing Center consultant. I’m studying English Literature with a minor in Poverty & Social Justice. At Elon, I’m part of the Honors Fellows program and a member of Danceworks.

Have you ever found yourself with a completed draft that doesn’t say what you want it to? Enter: the reverse outline.

The reverse outline is a technique for condensing a paper down to its main points. Often, seeing a zoomed out, deconstructed piece can help you see the forest for the trees. The piece will be less overwhelming if you break it down into its component parts, and this technique is useful for eliminating roadblocks. Reverse outlines are great for helping with organization and structure; they can help determine the effectiveness of a thesis statement or main idea and show you the strengths and weaknesses of your argument.

To write a reverse outline, start with a completed draft. Then, list one sentence or bullet point for each of the main points as they work in your draft. And remember, you can visit the Writing Center for help with this step. As you go, you might ask yourself questions such as: “Does each paragraph relate to and support my argument?” or “Am I repeating myself?”.

There are many reasons why reverse outlining can be an effective technique in the writing process. One good reason is that reverse outlines force you to evaluate how your ideas are actually flowing in a fully-written draft. They can help you determine if evidence is situated in its most effective place. Sometimes, reorganizing can get points you’ve already written to pack a bigger punch. Reorganizing becomes less overwhelming when you can clearly see the individual elements of a greater structured piece of writing, and that’s exactly what a reverse outline gets you.

You can also use them to make sure your structure is logical and all of your supporting evidence connects back to your thesis statements, which is critical in an effective piece of writing.

For more information, check out this article from the University of Wisconsin-Madison:

Happy reverse outlining! I hope this strategy works for you.