Beyond Spellcheck: How to Self-Revise a First Draft in a Time Crunch

Hi! My name is Zoë Rein and I’m a junior majoring in English with Teacher Licensure and Math with a minor in TESOL. Outside of The Writing Center, I’m an Honors Fellow doing research on writing and a director of Alternative Breaks! What is the last thing I feel like doing after writing my first draft?

What is the last thing I feel like doing after writing my first draft?

Writing the next one.

Going through the process of reading confusingly organized paragraphs, half-formulated ideas, and repetitive sentence structures is uncomfortable and painful. Sometimes, I think to myself that the first draft is “good enough,” and I can turn it in as is. Especially during those late nights or last-minute moments where The Writing Center and my friends are all asleep, it becomes easier to turn away and condemn the paper to its unrevised stage.

Yet, that early draft stage won’t pack as much of a punch as a well-organized, thought-out, and properly designed paper. Writing has the potential to change opinions, teach new ideas, and inspire creativity (as well as potentially get an A); but this doesn’t happen with just a quick glance at spell-check.

What does it mean to revise?

While many professors remind us to revise, I’ve learned that my definition of revision is, in fact, contrary to its actual meaning. I always thought of revision as just another look at my draft. Grammar concerns, spell-check, and word choice dominate my to-do list. If I’m in a time crunch, this feels like as much revision as I can handle.

However, this is proofreading, not revision.

Proofreading encompasses those last steps before you reach a final (for now!) draft, such as spelling, grammar, and punctuation. On the other hand, Walden University’s Writing Center, along with lots of other writing experts, remind us that revision is a more overarching process that re-analyzes a paper’s ideas and structures. It’s all about the BIG PICTURE!

Ideally, revision takes time and thought in order to focus on grand scheme ideas and elements of the writing. This is precisely why true revision terrifies writers like me. Revision requires vulnerable re-evaluation of thoughts that I already put effort into, so this stage necessitates deep engagement with words I love or hate. With the next draft, or drafts, I may add, cut, or rethink, making the journey to a final product an emotion-ridden roller coaster.

However, good intentions aside, I frequently find myself rushing to finish projects by trying to combine the writing stage with the revision stage. “Editing as I go” is a supposed time-saver, but it actually stunts the full extent of the process. Writing researchers Flower et al. distinguished amateur versus advanced writers because the experienced group spent the time to create a revision plan after the completion of a first draft (18).

In a world with no other obligations, a writer could spend weeks revising. However, we can still produce an impactful plan by choosing strategies that best fit the needs of our drafts. While it might be enticing to put down my laptop or let autocorrect do the work, I’ve found a couple of meaningful revisions can elevate a paper from first draft to final product in just a couple of hours.

Tip 1: Set your agenda

As Flower et al. found, agenda setting is crucial to understanding your individual revision process. Similarly, UNC Chapel Hill’s Writing Center suggests that each unique paper demands a unique next step. While these tips apply to common concerns, only you know your paper’s needs.

First, think honestly about your timeline. What prevents you from focusing on the paper? How much time can you and do you want to commit? In this timeline, how much can you accomplish?

From here, I suggest choosing three feasible areas to focus on. Select areas that would benefit from an extra 30 minutes, not just the sections that feel easiest to tackle. For instance, maybe you have a solid introduction, but the conclusion ends on a low note. The conclusion will gain more from the added attention even if addressing the introduction first feels more intuitive.

Try writing your essential three items followed by three additional possible areas if you have the time to focus on more of your paper. I like to write each task on a Sticky Note so I feel the satisfaction of crossing out completed tasks. I also make sure not to guilt myself if all I finish are those three essential tasks. This step is all about prioritizing, and sometimes that means not finishing everything perfectly!

Tip 2: Read aloud to re-hear

UNC’s Writing Center reminds us that to revise literally “means to ‘see again.’” However, equally useful is the opportunity to hear again! Reading out loud changes your perspective of the material you’ve thus far only seen on paper. One of the first things an Elon Writing Consultant (but also at Walden or UNC) will often ask you to do is to read your paper aloud.

While you’re reading, mark notes about what you think needs work. Listen carefully for organization in and between paragraphs. Does this paragraph completely diverge from the ones before and after? Does the sentence logically continue the argument?

Starting with this strategy also helps set your agenda. Whenever listening to a section makes me cringe, I know it needs to be in my to-do list.

Tip 3: Check your evidence and support

Evidence and supporting analysis will build the bulk of your paper. After all, most types of writing, whether lab report or literary essay, ask you to defend a big claim – your thesis – and several smaller, supporting ones. A professor once told me, “Don’t be a liar! Defend your thesis!” which UNC’s writing center rephrases as keeping true to your thesis with on-track and supported claims.

We can check that the paper follows through on the claims it makes as well as incorporates the appropriate evidence and analysis to make a balanced paper. UNC suggests keeping track of which points you emphasize or ignore. Although some points may naturally stand out more, try to equally weigh the paper (UNC).

Here are two strategies to check your evidence:

1. Reverse Outline

While reading through your paper, mark the margins up with the evidence and analysis you included for each paragraph. By the end, you’ll visually see which paragraphs have more or less support. You can use reverse outlining for many revision elements, so as you mark evidence feel free to add in notes about overall paragraph topics.

2. Mind Map

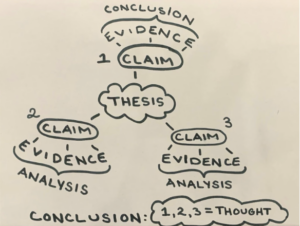

A mind map asks the writer to start with their thesis and then visually represent how their claims, evidence, and analysis fit together. After creating the map, you should see what points you use to back-up the thesis statement. Thus, you find if the points mesh with each other and the thesis. This strategy is especially useful if you like visual representations of your paper and find yourself struggling to picture how each element of your writing connects. Tip 4: Topic sentences

Tip 4: Topic sentences

My final tip is for inner-paragraph cohesion. This is a great step when you feel as though you incorporated solid evidence and analysis. Although reverse outlining or mind mapping promotes organization between paragraphs, you also must make sure the content in a paragraph aligns. One of my fatal mistakes while writing is creating an extra long paragraph that encompasses five loosely connected points. It’s almost impossible to remember the topic sentence’s argument by the time I finish!

I like to think of the topic sentence as the paragraph’s guide. Like the thesis statement, topic sentences usually make a claim or argument, and it’s the paragraph’s job to defend that all the way to the last sentence (see tip 3!). I like to quickly check for unity by first reading only the topic sentence and the concluding sentence. If the two make sense together, I know my paragraph is mostly on track.

Another more thorough strategy is reading every sentence and checking that it aligns with the first one in the paragraph. If you find that the paragraph splits into two directions, make them separate paragraphs! If you appropriately support your points, the number of paragraphs is not typically a concern. Breaking them apart may also help you find holes that you can elaborate on! If you feel like the paragraph shouldn’t be broken up, keep returning to the topic sentence until its argument is broad enough to sustain both sections of thought. And sometimes the topic sentence is the only one that’s different from the rest of the paragraph, and then you know that you just need to rewrite that first sentence.

Give it your all!

Revision can be a confusing and, frankly, frustrating process. However, devoting even one or two hours to your revision agenda will take your paper to a whole new level! Set a timer, find your writing mojo, and use these tips to make your work shine!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.