So, last week The Guardian online ran an article in the Global Development Professionals Network section, in which the authors sort of rambled on about the importance of discussing the sex lives of humanitarians. Yes, you read that right. A research fellow and an adviser at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) want to have a little chat about aid worker sex lives–that is, our sex lives.

On the outside chance that you missed their arousing discussion, check it out.

Yeah, yeah. Aid worker notoriety vis-a-vis all things sexual is legendary. I don’t think there’s any other aspect of the aid worker experience that is more commonly or gleefully portrayed in pop culture remakes of our allegedly exciting lives than our sexuality. From the apocryphal Emergency Sex, to the far-fetched tale of a UK housewive-turned-UNICEF warrior for the poor, to any one of several flaccid attempts to capture the aid worker experience as prime-time television drama, we see very quickly that the common denominator ain’t the Sphere standards for emergency WASH or an obsession with humanitarian accountability. My own first (and by far most commercially successful) furtive fumble down the path of humanitarian fiction shamelessly capitalized on the mythical hyper-sexualization of expat aid workers. Heck,even The Guardian’s own blush-worthy moment on the subject of aid worker sex life indiscretion seems to confirm exactly what everyone already thinks, and so we’ll forgive @IDS_UK for prematurely… er… raising the flag just a little too high on this one. Because, see, if you look at what actual aid workers are saying in the Aid Worker Survey, it would seem that we’re not really as busy getting busy as everyone seems to want to believe.

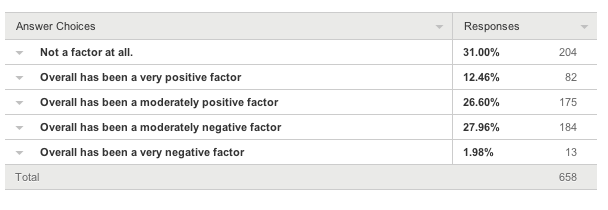

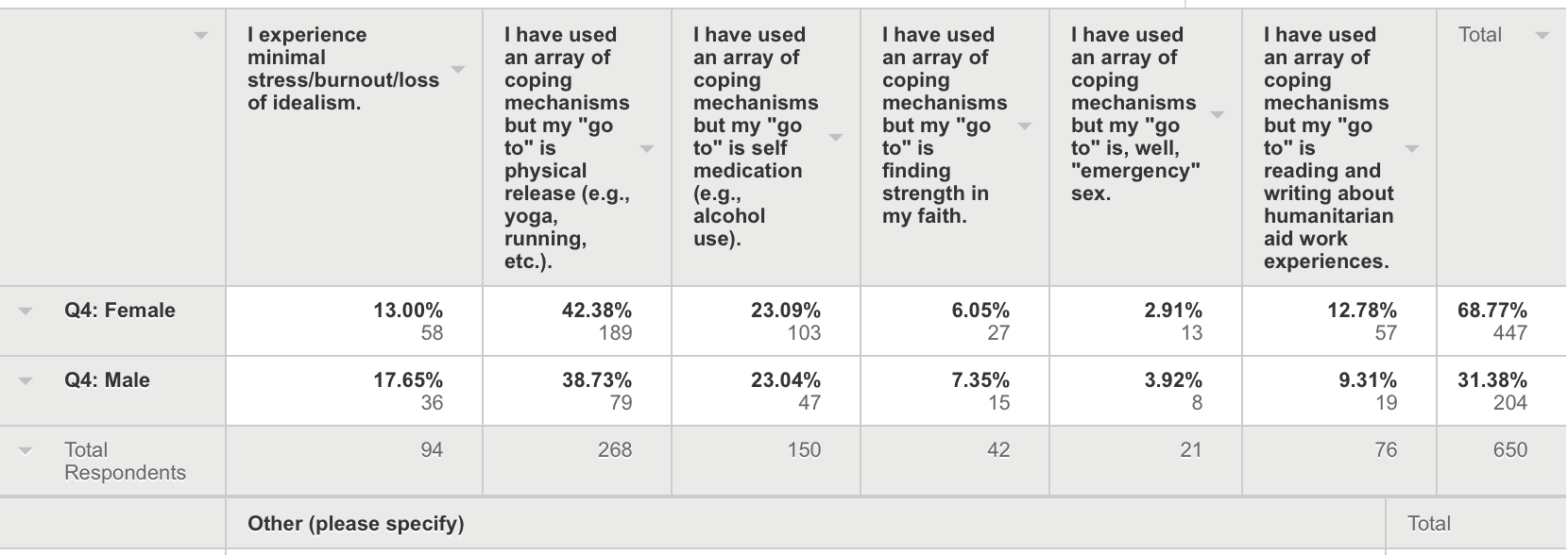

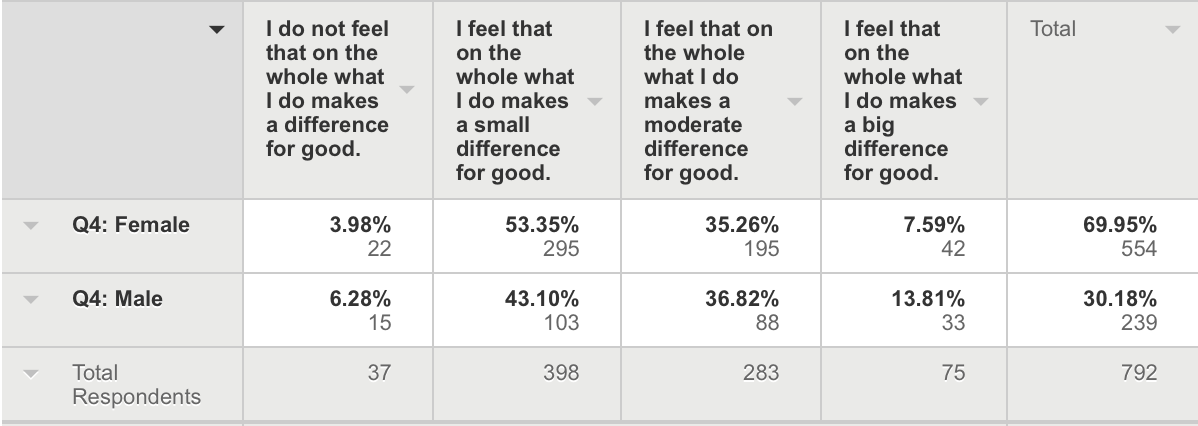

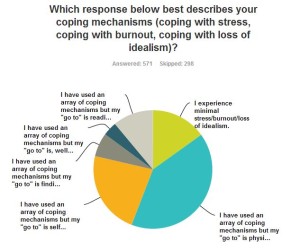

Let’s look at the results so far from Question 26: Which response below best describes your coping mechanisms (coping with stress, coping with burnout, coping with loss of idealism)?

[The response choices (paraphrased) are: I don’t experience burnout; Physical release (yoga, running…); Self medication (alcohol…); Finding strength in one’s faith; “Emergency Sex”; and Reading & writing about the humanitarian experience.]

I’ll skip straight to the spoiler: “Emergency Sex” scored dead last at 3.4% and 4.4% of female and male respondents, respectively.

The majority of all respondents (41% of females, and 40% of males) chose “Physical release“–yoga, running, or some kind of physical exercise as their primary stress release or coping mechanism. The remaining categories ranked as “Self Medication” (23% Female, 21% male), “Minimal Stress” (13% female, 18% male), “Reading/writing about the humanitarian experience” (12.8% female, 7.8 male), and “Strength from faith” (5.5% female, 8.5% male).

You can look at this breakdown in many ways. But for now, from a staff care perspective (and writing as a manager and frequent leader in field operations), I find the prevalence of “self medication” the most troubling in this lineup. In response to The Guardian’s hand-wringing, I’ll simply point out that according to our data thus far, it seems that more aid workers pray as a coping mechanism than engage in sexual activity.

This is the only question in the Aid Worker Survey which addresses or gives the option of sex, specifically, and so for sure we’re assuming a potential link between work or context-related stress and aid worker libido. Although the writers from IDS cover a wide range of aid worker sex related worries in their article (not just sex as stress release), on the basis of only the response data from Q26, it is reasonable to ask whether this really ought to be the first thing HR (or security, apparently) worries about.

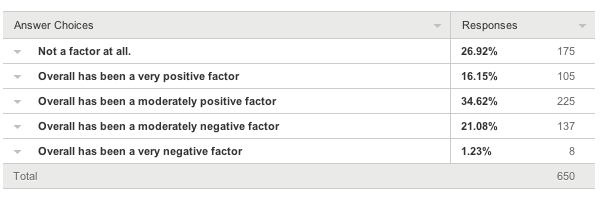

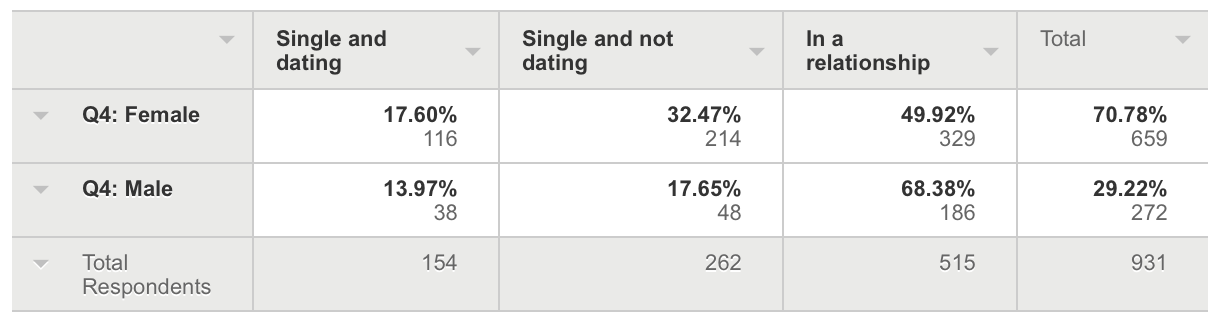

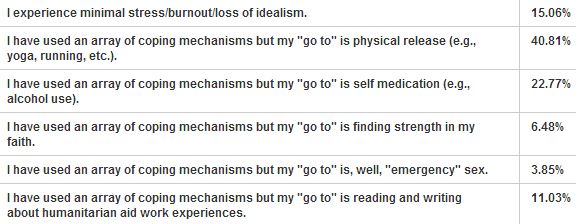

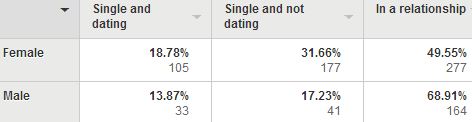

It’s also worth taking another look at some of the other data, too, though, with a view to the IDS’s angst about our sex lives. Q12 “Which best describes your relationship status?”, for example. The choices under Q26 are: Single and dating; Single and not dating; In a relationship. Here’s how it shakes out.

For the moment let’s assume that “single and dating” and “in a relationship” sort of hang together. In this context something like 68% of females and 83% of males are in some kind of relationship. No, I’m not naively assuming that dating or being in a relationship rules one out from participation in the alleged sexual misbehavior. Anyone can have a bad deployment, or just an evening of drunken (likely, according to Q26…) indiscretion, and of course there are those who are serially unfaithful. But based purely on personal observation as a long-term aid worker, it is my opinion that relationship status does make a difference. For all of their sometimes rough edges, aid workers are usually people of some kind of principle. Moreover, in my real job as a supervisor and frequent mentor to young newbs, I can tell you that there is no issue which comes up as frequently as relationships, specifically the desire for a relationship. When aid workers are in relationships–even relationships with challenges–the gravitational pull is toward doing everything possible to make those relationships work.

The ins and outs of aid worker sex lives will surely make interesting reading (to some). But that it’s something we must absolutely worry about now… well that’s a bit of a claim.

By hardly the second sentence into The Guardian’s article (written by those two researchers from IDS):

“…your day-to-day management challenges also included arguments over what time your colleagues could watch porn in the common room, and negotiating how staff could get to and from a brothel. Yet it is often a reality of the job and it is time we talked about it.”

Where to start? How about here: In a prior post, my research partner on this project described the “typical” aid worker, based on the results of this survey to-date. Once more with the spoiler: it’s a single, 30-something female. You can read the numbers in different ways (and we’ll eventually make raw data available in full), but basically the proportion of the single, 30-something women is above two-thirds of the total.

Based on the simple proportion of women to men in the industry overall, along with what we know from other sources about the propensity of men versus women when it comes to behaviors like paying for sex or consuming pornography, the statement above feels like a bit of overblown hand-wringing.

Also, I just have to say: in 23 years of continuous aid work, including quality time in some of the more notorious team houses in some of the more notorious responses, I have never (not once to-date) heard of aid workers watching porn in the common room. Nor have I ever heard of anyone ever needing the permission of the security manager before sleeping with someone from another other organization (see the caption under the photograph in the original article). And these days I usually supervise the security manager.

* * * * *

Surely some of the issues raised by The Guardian matter. The power dynamics involved and the potential for exploitation when aid workers become involved with local people while deployed (especially if they become involved with beneficiaries or disaster survivors) is terribly serious and worth larger, honest discussion. But a call for more discussion of aid workers’ sex lives (scintillating as that all might seem) needs to be grounded in some actual data, and framed in ways which correspond to real issues, rather than over-the-top, made-for-TV stereotypes.

* * * * *

Think I’m wrong? Sound off on in the comments thread below this post, or on my Facebook page, here.

Want to take the Aid Worker Survey yourself? (of course you do) Do it!

Take the Aid Worker Survey in Arabic.

Take the Aid Worker Survey in Spanish.

Follow

Follow