What do you like -or not like- about being an aid worker?

“I don’t like that people see what aid workers do as “charity” work. I am not a socialite here for the feel good factor. People don’t actually acknowledge that this field is a “real” career.”

“Sometimes you wonder what the hell you’re doing, and why. Sometimes I think that aid is categorically harmful and we should all pack up and go home. Other days I don’t feel like this.”

-female expat aid worker

“Hate the feeling of inequality, being patronising, being seen as the rich white girl, etc. But like the feeling of being somewhere that matters. And meeting people – the basic human interaction with people across the world – love that.”

“Urban cholera outbreak – I am secretly excited. I know it’s wrong but it’s what I do and I’m good at it. Aid workers are macabre like that.”

What do you like -or not like- about being an aid worker?

Cathartic moment

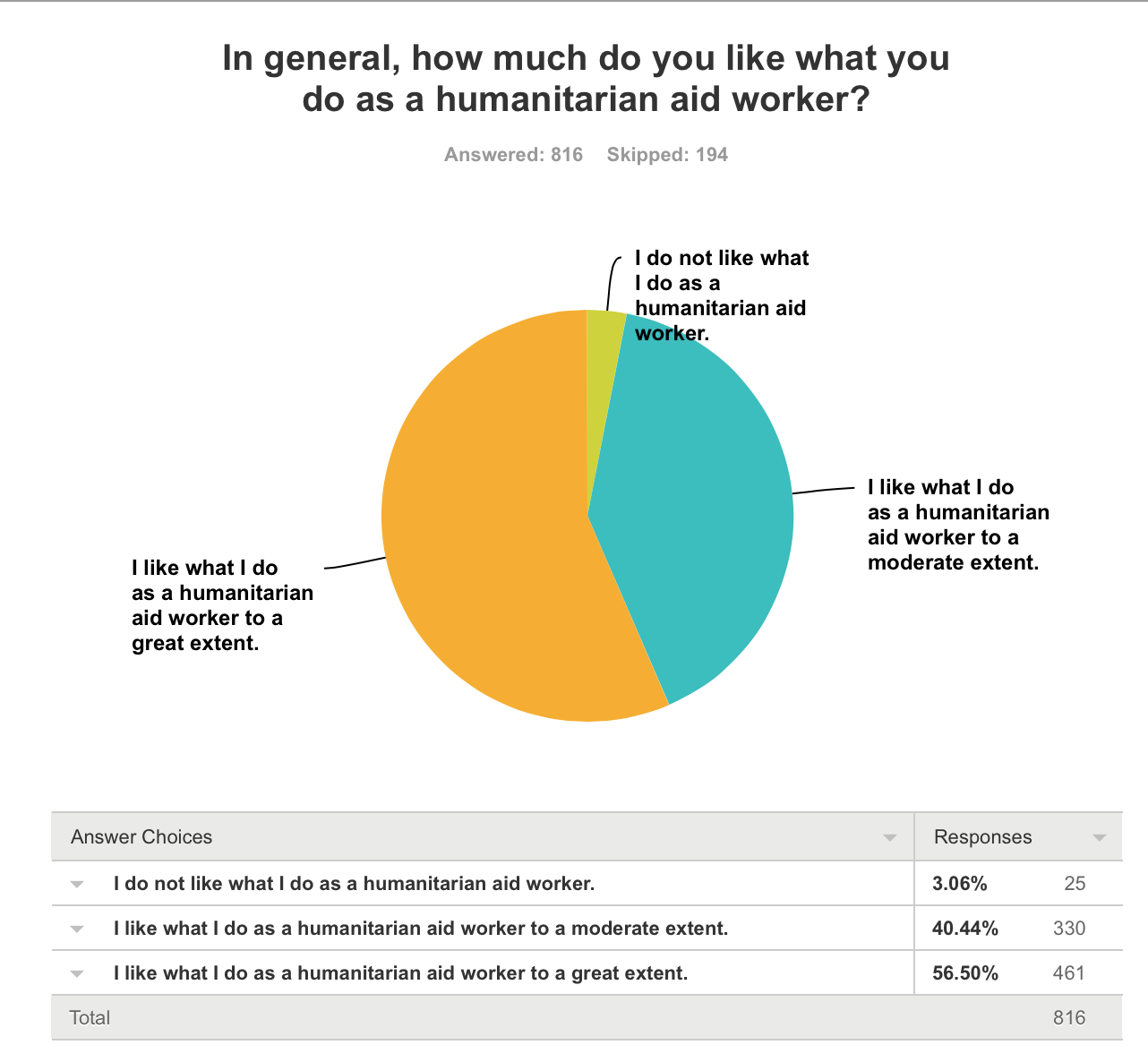

In the middle of the survey were two questions included to provide data for us and a cathartic moment for those offering their input. Q30 asked “In general, how much do you like what you do as a humanitarian aid worker?” and Q31 invited the respondents to “Use the space below to elaborate on what do or do not  like about being a humanitarian aid worker. An illustrative anecdote will be useful, perhaps.” That over half (433) of those who responded to the closed ended question (816) took the time to follow up with elaboration and example is evidence of a need for the cathartic function of these specific questions and perhaps the survey as a whole.

like about being a humanitarian aid worker. An illustrative anecdote will be useful, perhaps.” That over half (433) of those who responded to the closed ended question (816) took the time to follow up with elaboration and example is evidence of a need for the cathartic function of these specific questions and perhaps the survey as a whole.

One female aid worker summed up her feelings this way.

“This has been a very interesting and thought-provoking process for me. I realise that I have become more cynical in some ways and at the same time more hopeful. Even with middle-age bearing down on me like a drunken uncle at a wedding, I’m still with Elvis – “what’s so funny about peace love and understanding?” and still idealistic enough to believe that it is not only possible to change the world but that the point is never to give up trying.”

Another noted, “This is a great survey. The questions really dig into the issues and doubts at least I as an expat aid worker face.”

This one sums up the feelings of many caught in the immediacy of the now, I think.

“Very interesting survey and I appreciate the chance to share my views – it is surprising how little time (and few opportunities) one has to actually *think* about things in the busyness of the day-to-day. I wish your survey results could be shared in an open forum (not only virtual) where significant players can be present and honestly reflect for a moment.”

The results on these two questions are rich with thoughtful perspectives regarding the aid sector in general but more dramatically with a insights about how aid workers feel about their jobs and their lives doing this kind of work.

First the quantitative data

Reading all 433 narrative responses after seeing the numbers below was a bit of a disconnect as you’ll see below. The numbers suggest that, on the whole, our respondents like what they do, with 57% indicating “to a great extent” and another 44% at least a moderate extent. If my math is correct, that means an overwhelming majority -97%- of those responding to our survey like what they do. That said, “liking” and “being snarky/critical/cynical about” are not mutually exclusive.

What do aid workers like about being in the sector?

Given the quantitative data results above, I expected to read volumes of glowing anecdotes about being an aid worker. There were many, indeed, though many of the voices included both positive and negative and sometimes these were the same things, as in this comment.

“The change and variety is something I like and don’t like at the same time. It keeps things interesting and sometimes exciting but having to adapt frequently gets tiring. I like meeting new and different people. I like seeing new places. I get to talk about things I like. I don’t like being away from immediate family and friends.”

This next one critiqued the word ‘like’ in our question and captures the sentiment of many with her words about how the job makes her feel.

“People ask whether I ‘enjoy’ or ‘like’ what I do. I always find that a very hard question to answer. Enjoy? No, not really. It can drive me crazy at times, but it’s what makes me feel most alive. There’s a depth of experience not often found in a ‘normal’ job in the UK. The things I don’t like would be similar in any role, e.g. dealing with difficult colleagues.”

I love the phrase “niche parts of the human experience” in this next one.

“What I like most about being an HAW is that I find the work I am able to be a part of extremely meaningful and compelling. I have the privilege to bear witness to and affect change to some niche parts of the human experience. I find one of the most difficult parts of the job to be coping with the stress and the feeling of disassociation.”

This next respondent makes an interesting distinction between being and doing.

“It’s not that I like being an aid worker. I like to do things that utilize the skill sets and strengths I have — being adaptable, empathetic, culturally sensitive, organized, and analytical. I like to engage issues that I feel passionate about. I like work that reflects my own values. Aid work allows me to do all of that.”

I found that many did not like what the sector did in terms of their personal life yet felt good about the contributions they were making. Here is a perfect example:

“I like knowing that I make a difference in people’s lives and that I’ve prevented suffering. I like being amongst like-minded people. I like that I don’t have to get a mortgage and do the same mind numbing work in an office in the same place every day. I don’t like that I can’t keep cats as pets and that relationships are always complicated by work and distance.”

These next two highlight the satisfaction that comes from the simple act of connecting with other people.

“At the end of the day, I love analyzing large social problems and trying to identify ways to solve them, in community with other people. I appreciate the human connection that is involved in my job, and the relationships across boundaries that can be developed.”

“It is the small moments for me that I like. Getting national staff recognised or promoted in an organisation. Giving a tarpaulin to an old lady who has lost her roof. Taking a football to a group of children and playing with them. That moment when someone comes to you and says ‘Thank you for coming. Nobody else has.’ Accepting a mango from someone who is so poor they don’t even have a shirt, because they insist they get to show their appreciation somehow. Watching a group of young men build a bridge with materials your project provided, and having them laugh at you when you join in and can’t even move a full wheelbarrow. Any positive interaction with national staff and beneficiaries. And randomly bumping into a colleague at an airport bar and discussing the most recent locations of common friends and then detailing your latest gastrointestinal mishaps and tropical diseases.”

This one touched me as I read it, and I still am at a loss as to how to respond.

“It depends on the day and/or hour. Example: In the morning I am trekking through the mountains to visit a classroom and train our M&E officers. In the evenings, I am sitting alone in a mud-walled compound eating the same beans I have eaten for the last 3 weeks and silently sobbing myself to sleep.”

As with other sections on the survey, this question brought out a thoughtfulness that is striking. This one represents many that mention liking “making a difference,” travel adventures and the challenges they face in their jobs, how their work is misunderstood, “good” aid versus “bad” aid, and finally, the frustration of dealing with donors.

“I like the feeling of making some sort of difference in people’s lives. I like that I am constantly exposed to new adventures and new challenges. I like that I’ve gotten the opportunity to live and travel in all sorts of places most Americans have never heard of. This was a career change for me about 6 years ago,  getting away from the corporate world, and I think it was the best thing I could have done for myself. I don’t like the fact that everyone assumes I’m an English teacher when they hear I work abroad. I don’t like that some organizations seem to be doing more harm than good and even though I don’t work for them, I’m still lumped together with their aid workers. I don’t like the way some aid is forced to be based on donor interests and not necessarily what’s best for the community.”

getting away from the corporate world, and I think it was the best thing I could have done for myself. I don’t like the fact that everyone assumes I’m an English teacher when they hear I work abroad. I don’t like that some organizations seem to be doing more harm than good and even though I don’t work for them, I’m still lumped together with their aid workers. I don’t like the way some aid is forced to be based on donor interests and not necessarily what’s best for the community.”

Many talk about the joy of specific accomplishments and small ‘victories.’ Here’s a detailed comment that illustrates just that.

“I like meeting with the direct recipients of our work (we work on repairing obstetric fistulas, a very specific facet of maternal health). I like getting a better understanding of the environments in which they live and learning a bit about their lives, rather than reading all the worst-case scenarios we’re inundated with in the media. These are real people with real smiles, real problems, real senses of humor. I especially like candid conversations with the surgeons we work with and with the “local” aid workers we partner with. Nothing ever goes quite as planned, and it’s usually the conversations over a beer or in a quiet, un-planned moment that give you the best information.”

What don’t aid workers like about being in the sector?

Many talked about frustrations dealing with bureaucracies and especially with donors. Here are some representative examples, the three showing an awareness of a fundamental truism regarding bureaucracies, namely that there is an inverse relationship between size and flexibility.

“I absolutely DETEST the fact that we are called upon to feed the machine of HQ (media and comms) and that our size has now brought us to the point of creaky inefficiency instead of speedy lifesaving responses.”

“I do not like the bureaucracy and lack of innovation and creativity that seems to be hard to implement at many of the larger organizations that fund most of aid (e.g. UN agencies, USAID, etc.). I also do not like how, try as we might, the people we aim to help still seem to be lost and forgotten in the conversation. For example, if a community health worker or short-term volunteer is paid $5 a day to help us, is that really improving the person’s livelihood, or are we just using them to achieve our project’s goals?”

“Sometimes it [aid work] is incredibly rewarding, but it can also be incredibly frustrating, particularly when one is stymied by bureaucratic inertia/ineptitude that prevents being able to respond effectively.”

“Frustrating amounts of bureaucracy, poor communication, etc. lead to a decrease in the quality of services provided to targeted populations. This is frustrating.”

These next two are especially critical of and frustrated by donors.

“I am frustrated by donors who push an agenda — a checklist — with no recognition of the limitations faced by the beneficiaries.”

“I dislike dealing with funders who try to control projects with extremely narrow parameters and don’t understand how the projects often have to adapt to accommodate shifts in contexts; but I especially dislike funders who say crap like ‘I want to come see the poor knocked up teenage mothers’. First, keep your damn money, Second: No; they are not animals in a zoo; and Third: Seriously? I am so over this post-2015 malarkey: it is such a waste of resources and energy; especially when every development agenda that has been formulated since the 1970s is *still* unfinished…”

“My work on the ground with people who need and appreciate any support they can get is very rewarding. At the same time I hate the amount of bureaucracy I have to deal with and the competition between different aid organizations. Sometimes it is also sad, that projects are failing for different reasons.’

There are many who refer to a frustration for knowing their efforts could be more effective but that there is in invariably a gap between the is and the ought, the ways things are and the way things could/should be in a perfect world. This woman is one of many who show a keen understanding of the bigger picture but are challenged by the fact that the reality that we live in a world dominated by political forces and maddeningly inflexible bureaucracies.

“I work with great, intelligent and committed people but development work is bureaucratic and frustratingly political while pretending it is apolitical. It is complex and messy but politicians want it to be quick and ‘results-oriented’ in unrealistic timelines. It often tinkers with things rather than asking difficult questions about wealth and poverty; have and have nots or asking if we need to fundamentally rethink how we have imagined our world.”

This veteran male aid worker sums up perfectly what many voiced in different words.

“The gap between the narrative the aid industry tells about itself, and the reality.”

And now for the snark

Below are some representative comments, the first few adding to the reputation of aid workers being, well, snarky.

“No brainer. The politics in it. Shocking. Laughable levels of discrimination. The blindness to privilege, power and responsibility. Do I like my day-to-day work? Hell no! I am in HQ. Far removed from most things remotely interesting and bang in the middle of the BS that characterizes intl. dev. Plus everything I do is beyond my control. I fight battles that I have already lost in a war that is never-ending.”

I do is beyond my control. I fight battles that I have already lost in a war that is never-ending.”

The comment above underscored what I have found as a theme throughout all of the data, namely that there is a frustration with control over the outcome of one’s efforts and the sense that as an individual the aid worker is ‘only’ part of a bureaucracy within a sector dominated by even larger, intertwined bureaucracies which are in turn impacted by political, economic and historical forces beyond anyone’s control. These next two comments are same sentiment, different wordings.

“The mind-numbing, soul-numbing, stifling layers of bureaucracy. The pretense of it all. The hypocrisy and peddling lies. Everyone pretending to care when everyone is really around the table to please their paymaster (direct boss or donor) at the end of the day. The matrices and RBM word smithing. Needing to fill out multiple and contradictory bureaucratic reports to address every donor demand ever made over the years. Being a cog and not really being able to have a personal say. Losing yourself and independence to the collective. Perfunctory tasks and meetings. Turf wars. At least in private sector there is a handsome pay-off, but in our work it’s all the more pathetic bc it’s not worth it – it’s just petty egos. Also the pretense behind the New Snarky Aid Narrative that portrays the white western aid worker as a clown vs. the wise local. That’s bullshit too. Locals/nationals are not off the hook in any way – they don’t get carte blanche and auto-cred. They come with their own class and racial baggage internally too. No one is innocent here. No one gets a free pass.”

The last couple sentences above are particularly on point, methinks.

“not like: being shout at by hierarchical superiors. being a threat to their incompetence. lacking tools to work. feeling a cog in the machine, or a lemon to be pressed till exhaustion before being thrown to the rubbish bin. The arrogance that makes the sector think they can save the world, and without professional competence. The lack of privacy, being always “a child” . Living with colleagues. Abuses that would get someone fired in the private sector here can get land them a better position. I like: discovering new realities, learning about humans and their ways of living, coping, leaning from others.”

“I do not like telling people what to do with their lives, even if only by implication. Moreover, I don’t like the sanctimony and hypocrisy inherent in an industry that’s ostensibly about “service to the poor” (and other such self-congratulatory rhetoric) but in fact serves primarily to support comfortable lifestyles for people from rich countries who want to feel like they’re doing something more meaningful than their investment banker classmates.”

And final words from the dark side?

“I like the cultural context, specifically related to nutrition and feeding practices. But sometimes everything just seems like a well intentioned clusterfuck.”

“It’s a job, at the end of the day. I’m in it for me – we all are. I just hope others benefit from my selfishness, to a higher extent than if I was in another job.”

“Aid work still has a dark side – winning over donors and competing over space. Every new disaster is like the moon-gotta get that flag up 1st. Can’t we just get along while getting work done?!?”

Conclusions?

Of the 433 written responses to this question several stuck out in terms of the breadth, depth and thoughtfulness of what they write. This first one, I think, does the best at summarizing the complexities regarding how aid workers feel about their jobs and lives. Her “likes” are rich and complex.

“I like the complexity and power of the issues I face in my work. I know its potential to have a real impact on people’s lives and I strive to see that realised in my work. I also find it stimulating in various ways that resonate for me – issues at the heart of humanity, aspects of spirituality (although I’m not religious), intellectually stimulating, understanding different cultures, religions, histories, etc. I have met some truly remarkable people. All of this has indelibly changed who I am.

Her “dislikes” strike deeply, and I am touched and saddened as I read…

“I don’t like the politics of the work – dealing with people who care more about their careers and reputations than doing good work. I wouldn’t call it frustration with bureaucracy, it’s frustration with pettiness, apathy and cowardice. At the worse end of the scale, I have met and worked with some of the worst people I’ve ever known. They have been corrupt, spying for government, sexually exploiting staff and community members. But typically it’s just working with people who refuse to take risks to improve responses because they are more concerned with their own career goals. As most of my work requires coordination and consensus-building, these people can make it impossible to do good quality work. And they’re not a small minority, unfortunately.”

This next one tips more toward the “dislike” in making some good points reflecting the general frustrations of many.

“I like to interact with local staff, and try to position myself as a friendly channel for feedback and information to senior management. I enjoy helping them find training opportunities and teaching them whatever I can. I enjoy designing projects and talking to local partners about their ideas. I enjoy interacting with my colleagues and finding our way around challenges. I do not like cluster coordination meetings, UN workshops, UN turf wars over things like CERF allocations, leadership who are fixated on competition with other agencies and who are jealously protective of information rather than being collaborative and open. I do not like the bullshitting and manipulation of facts that is involved in the reporting process. I really hate the ‘re-coding’ of massive amounts of funding as projects come to an end; and equally the rapid, massive purchases that can occur in order to spend an underspent budget. I don’t like the constrained timelines for longer-term development projects (social change in 18 months? really?), the fact that donors refuse to provide funds for training of staff, or the patronising attitude of iNGOs and UN towards local NGOs.”

One main point made above is that social change -and that is what development work is in essence- cannot be rushed. I would hazard that most in the development world would say ‘amen’ to her point.

Finally, this last one is a sideways comment on aid work, critiquing the fundamental nature of the sector and arguing what most of us know already, that, in the end, change comes from within the community.

“I don’t consider myself a humanitarian aid worker (so the question above is a bit awkward). I really didn’t like what I did in a traditional humanitarian organization – it was so disconnected from any sort of reality I could grasp, even though I was “in the field” every day. So I quit and began to work with a much smaller group, doing development work at a much smaller scale in [section of city], where I was living at the time and had a connection to. This was so much more grounding and rewarding because when things went well, I actually felt it in my everyday life, and when things went wrong, I also felt it. Being connected to your work in that way is so much healthier than the “humanitarian” work I was doing before, because these places only existed during the working day and we were really not connected to the consequences. But when I worked in and with communities that I had developed relationships with, I understood how long change takes and how much it has to be owned and driven by people like my neighbors, and it helped me lose the sense of needing to be in control that so many humanitarians have (hence why many of them get stressed and smoke lots of cigarettes). Now, my work is less “sexy” and “exciting” than it was in the “humanitarian days”, but it’s so much more real.”

Last thought

What I see in toto as I read all of these responses is, above all else, the words of those who care deeply about what they do and about those with which they work. They enjoy living their convictions and thus endure the frustrations inherent in their jobs.

As always, please contact me with questions or comments. @tarcaro on Twitter.

Follow

Follow