Female aid and development workers: how is gender a factor in their work?

Female aid and development workers: how is gender a factor in their work?

Context

I have previously written two posts having to do with the male-female differences in our survey responses. Check here and here for these posts. I turn now to the results from our specific questions about the impact of gender.

Two questions

Which of these four factors is the most important in influencing how we see ourselves: race/ethnicity/cultural status, social class/relative wealth and power, gender or age? Which of those four factors is the most important in influencing how others perceive and react to us?

Certainly every one of these factors is critically important for all of us no matter where we are in the world or what our occupation might be. Indeed, that is a basic truism in the social sciences. Though Max Weber was referring more narrowly to wealth and power when he first used the term, his concept of “life chances” can be usefully applied more broadly to all four of these factors. Each can and frequently does play into how we go through our lives and our work days, that is, what “life chances” we enjoy -or don’t enjoy- depending upon where we are vis-a-vis these four major social variables. Which factor is the most important for an individual can change quickly, even moment by moment as we transition from one social setting to the next, for example getting off a plane to a deployment faced with immediate and dramatic cultural shifts. In short, all four factors are critical, and various combinations can lead alternately to open or closed doors.

This comment from a young, white, male expat aid worker sums this point up nicely:

“In Muslim countries, being a male makes a lot of things easier, even though in West Africa you are generally perceived as white before being perceived as a man or a woman. The only disadvantages in being a Male in some unstable countries are that it makes you more of a target for ‘extremist/hostile’ groups in some contexts.”

That one’s perceived gender can influence how a person is responded to is the focus below, and by presenting some representative narrative responses from our survey I hope to shed light on the deeper contextual nuances of perceived gender identity.

As a related note, how you feel about yourself is influenced by how you believe others are seeing you and how they are evaluating -judging-what they see. Perhaps that is part of the allure of being an aid worker: “How wonderful you are to help other people!” Though the “looking-glass self” can have that positive side, when the way you are perceived by others is negative (“When two thousand years old you are, see how many times a week you are accused of being ‘too male, too pale, stale.'” stated one male respondent to our survey).

To go one step further, looking through the lens of sociologist Irving Goffman’s concept of “impression management” when we are at home and/or in our cubicle environment we are able to use myriad props, cues and affectations to enhance -or mute- any or all of our gender, race, age or class statuses. We are in control somewhat of how we are seen by others and can manipulate -albeit most times doing so unconsciously- the looking-glass effect, somewhat. By stark contrast, while in the field there are times when we have very little control over how are are perceived. One important interpersonal skill any aid worker must have is the ability to imagine what people in an array of contexts see when they look at them and then act in accordance with that knowledge.

Some results

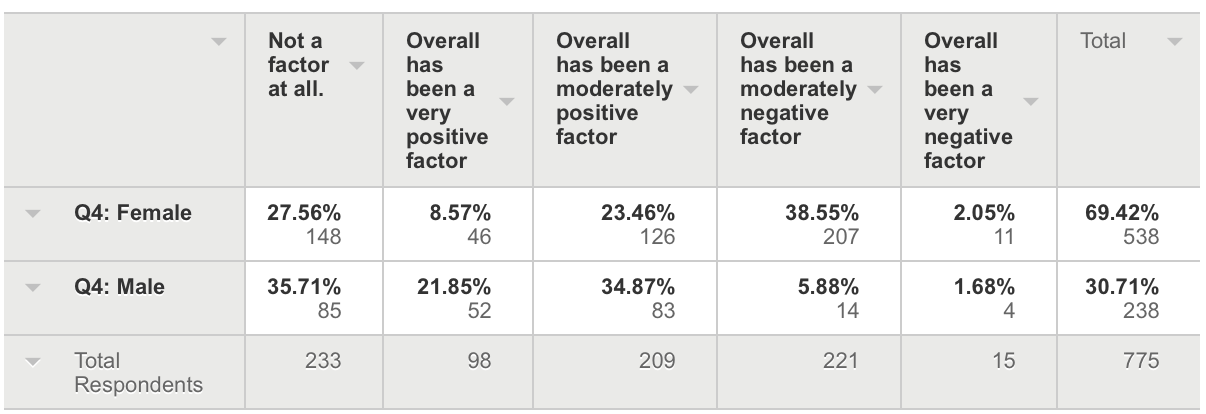

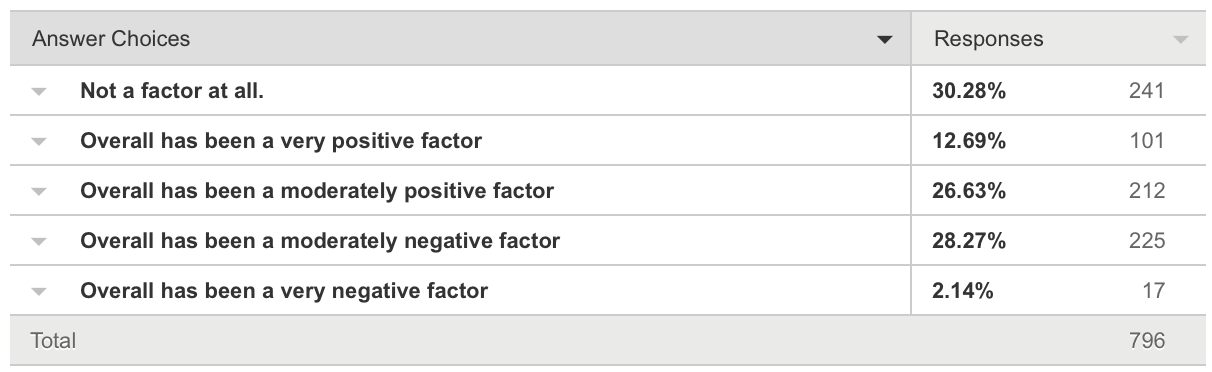

Below are our results to the question related to gender being a factor for aid or development workers. I am a bit surprised that nearly a third -30%-  of the respondents indicated their gender was not a factor at all in their work. When broken down by male compared to female, the percentages differ in what I would consider a predictable manner with females lower at 28% compared to 36% for males. I can understand that a male might not be habituated to thinking in terms of gender, but for well of a fourth of the females to report gender not a factor sounds, well, a bit odd, especially as I look more closely at the other numbers and read through some of the comments that were offered in the open-ended followup question (Q41).

of the respondents indicated their gender was not a factor at all in their work. When broken down by male compared to female, the percentages differ in what I would consider a predictable manner with females lower at 28% compared to 36% for males. I can understand that a male might not be habituated to thinking in terms of gender, but for well of a fourth of the females to report gender not a factor sounds, well, a bit odd, especially as I look more closely at the other numbers and read through some of the comments that were offered in the open-ended followup question (Q41).

What we do see very clearly in the data below is that that by a very wide margin gender is a more negative factor for females than for males, with 39% of the females indicating that their gender was a negative factor compared to only 7% of the males indicating the same.

Q 40: To what extent has your gender been a factor in your humanitarian aid work experience?

Qualitative data

Among the 328 (thank you all!) women that provided a response in the followup open ended question (Q41) several themes and patterns emerge.

Gender impacts both relationships with colleagues in the aid worker industry and those with the non-aid workers (both aid/support beneficiaries and non-beneficiary community members) in both negative and positive ways. Below are examples.

- “It’s been creeping up on me … I never thought it is an issue but over the years I did notice that it is. Either with project clients and sometimes with colleagues.” (30+yo female expat aid worker)

- “I would say the positive aspects outweigh the negative. As a woman, I have been able to work with women and children in communities more closely than if I was a man. I also feel blessed to have close female friends in this field and we try to support and nurture each other as much as possible. I have not witnessed men bonding in this way. However, I have experienced sexism and harassment quite a bit in the course of my work. In some countries the harassment was significant and carried with it the threat of violence. On a couple of occasions I have not received jobs due to my gender. I have also experienced female bullying.” (41+y0 female expat aid worker)

This next one gets pretty specific and expresses anger that I suspect may generate some head nods among the women reading this post.

“Because white women like me can still be viewed negatively, dismissed, ignored, by other white men – yes, really. So, a white woman in a senior position in Africa? Tough. African men ignore me routinely, especially if I am in the company of a male colleague, I may as well not be there sometimes. Only when they realise they need me to get to the money, do they talk to me. By then it is too late. Enough assholes in aid work, I am not supporting those who do not acknowledge a white woman.” (31+yo female expat air worker)

The next two examples highlight the nuance of gender impact.

- “My answer will change based on the day. It is definitely a large factor but in some instances it is positive and in others it is negative. I deal regularly with sexist rules and comments made by other expat staff members who I am sure do not even realize what they are saying or doing (e.g. no you cannot ride a bike, no you cannot drive a car. you are too emotional you must not be able to cope with stress. no you cannot attend this meeting with us, etc. etc.) When dealing with locals I have found that being a woman is often a positive as people seem

to open up and trust women more than men and are more likely to feel they must take care of a woman, therefore offering me more access to people’s homes to be able to talk to them.” (41+y0 female expat aid worker)

to open up and trust women more than men and are more likely to feel they must take care of a woman, therefore offering me more access to people’s homes to be able to talk to them.” (41+y0 female expat aid worker) - Being a woman can be exceedingly difficult, especially in conflict zones where I’m working with mostly men. All of the decisions are based on a 2-dimensional perspective. It takes a lot of explaining to bring about a holistic approach and/or incorporate the lives of women in planning. Sometimes, as an expat woman, I’m considered androgynous and given the same access as a male. But that can also be isolating, depending on the context since I end up in the male category and have to fight to speak to a woman or plan things that factor in women’s lives. Sometimes, I’m a critical bridge between the women/vulnerable and decision makers, a “voice” for women when they’re kept out of the process. That can also be a burden if decision makers are expecting you to be the voice for millions of women. (40+yo female expat aid worker)

Addition thoughts

Here are some additional responses:

- This was a challenging question. While I don’t feel I have ever been discriminated against for being female in my job, there are certain implications. In my organization, the majority of staff at HQ are actually female – so I am at a slight disadvantage were I to try and work at HQ. In the field it is different – there are some perceptions by male coworkers that some deployment areas are ‘too dangerous’ for women so this can limit your movement.

- I have experienced sexual harassment from “locals” and staff alike too many times to count. I have at times felt like a liability to male staff when confronted with armed groups who use the threat of rape and kidnap of females as pressure to get what they want. I also believe my gender has enabled me to connect with children despite language barriers and open conversations that may not have happened otherwise.

- Sometimes positive (interviewing female participants) and other times more dangerous.

- In my organization, “rank and file” staff at HQ level are dominated by young women, whereas senior managers and leadership continue to be dominated by men. This is changing, but still observable. In the HQ setting, being a driven female was positive because my motivation was rewarded with opportunities. In the field, the overwhelming majority of “rank and file” staff (local nationals) are men, as well as heads of local organizations and government, and often fairly traditional. This made being a senior leader challenging at times, as I had to work harder to earn respect from my male counterparts.

- The only issue that my gender has caused is that it was a factor in deciding whether or not to go to work in Afghanistan. That’s the only time it has influenced any decision I’ve made.

- Being a woman can sometimes help in communication and negotiation

- I think as a woman, there are still issues in respecting me in some cases, likely. I think my age (I’m still young compared to most local colleagues) has probably been a bigger factor than my gender though.

- In a lot of countries being a woman means working ten times harder than men just to be taken seriously (even by your own colleagues). And I have been in situations when me being a woman put me in more physical danger.

- More risk associated with being alone/out Sometimes I get the sense that people don’t take what I’m saying as seriously, and I noticed they’ll look to or defer to the man in the group, even if I’m the one in the position to answer/position of authority.

- When I am able to work directly with poor or marginalized women in visual storytelling processes, my gender creates a more open and safe environment for them. As such, I always ask for a female translator, if needed, when working with women.

- It’s been difficult in two ways: 1. There is certainly an “old boys network” in my work context. My bosses are more likely to listen to other male workers’ opinions, especially on academic or theoretical topics. 2. Being a woman in a Central American context is frustrating on a daily level (catcalls, threats to security) which I think decreases my productivity.

A take-home thought

Being a female aid worker is, in sum, not the same as being a male aid worker in many, many ways. The quantitative results from our main question highlighted the fact that one’s gender is more of a negative factor for women. The qualitative data produced the insight that though there are negatives and positives of being a female when working with colleagues as well as with clients and locals, the negatives working with colleagues were much more commonly cited than the negatives when working with clients or locals. Indeed, what I am reading is that in terms of doing her job, being a female was frequently a distinct disadvantage.

What is the take-home point from all of the above? Aid and development organizations recruiting and hoping to retain qualified females need to be constantly aware of the impact of gender and ceaselessly work to minimize the negatives in whatever ways they can. They should begin by hearing the voices of the women already in their ranks and using their insights and growth to support those who come behind them, both males and females.

In my next post I’ll drill deeper into the impact of all of the social variables on the lives of aid workers. We are as others see us, like it or not.

Thoughts, questions or comments? Reach me via email.

Follow

Follow