Skimming off the top (part 2)

Skimming off the top (part 2)

In my last post I began ‘skimming off the top’ of the data, highlighting what are the common/modal responses to most questions. As promised here’s part 2 covering more of the questions.

**********

Questions 33-38 all focused on a what I believe is a constant -though evolving- issue for most aid workers, namely how to communicate what they do to those most important to them: their significant others, children, family and friends. We all have a basic need to be understood by those around us, and the closer that person is to us, the more important that need. All aid and development workers tend to compartmentalize to a greater or lesser extent just to get by, but the coping mechanism of separating the ‘job me’ and the ‘relationship me’ is inherently disingenuous and potentially a red flag in any relationship. Being in a primary group with someone means that by definition you share your emotional lives, and that clearly would include what happens to you at work.

Q33 asked about the difficulty in explaining to non-aid worker non-significant other adult family members the nature of the work being done in aid and development. By a small margin, the modal response was “I have some difficulty explaining my job, but it can be done” (38%) with a close second (37%) saying “I have some difficulty explaining my job, and can only articulate a general sense of what I do.”

These responses illustrate some complexities and differing perspectives:

- “Family at home don’t have a reference frame for what it means to live in the places I do. They lose interest very quickly when I try to discuss my job, so I keep it general and very light.” (31+yo male expat aid worker)

- “Tried and failed to come up with the elevator pitch, failed to come up with the 5 minute pitch even. Have boiled it down to just “economics” [which] means very little and no one asks follow up questions.” (30yo female expat aid worker)

- “My adult family members question the difference between development work and the invasion of Afghanistan, feeling both are western imperialism – one just happens to be at gun point.” (31+yo male HQ worker)

This last response raises a host of issues related to the complexities of not just explaining one’s job but also the risk of having to  defend it as well. This is an issue well worth further examination and explication.

defend it as well. This is an issue well worth further examination and explication.

Q35 asked, “Which statement below best describes your ability to explain to your significant other the nature of your job?” and by far the most common response was “I have some difficulty explaining my job, but it can be done.” The results of this question were confounded by the fact that many aid workers reported not having a significant other and/or their significant other also works in the same or very similar field.

Here are a couple illustrative narrative responses, the second one containing a gem of insight about aid workers in general:

- “The significant other also has a high-stress job and is quite smart – so I make comparisons. Plus, he’s actually interested so it helps.” (31+yo female HQ worker)

- “My husband is not an aid worker but is a human rights advocate and has worked in the sector for some years before he became an academic. He still doesn’t understand nuts-and-bolts things about my job but he understands the big moving pieces and it helps tremendously to talk with him at a more philosophical level; in some ways easier than talking with other aid workers – we are an idiosynchratic bunch with lots of competing motivations.” (35+ yo female expat aid worker)

Q’s 37 & 38 focused on explaining the work the respondent dies to children in their lives (“non-adult family members) with a somewhat predictable -but none the less distressing- majority indicating that “I don’t even try to explain my job.”

This 35+ yo female expat aid worker, though certainly not representative of many in her same situation makes a wonderful point.

“My children (5 and 7) think my job is to work on a computer. During my last field posting, I took them to project sites from time to time which helped them connect the dots. But interestingly, through their eyes they did not see the poverty or the “despair” that NGOs like to market to their constituents – they played with other children, ran around together, they connected in a human way that we “aid workers” often fail to do.”

Though the work carries with it some liabilities, the overwhelming majority (80%!) respondents to Q39 said that if someone close to them (a child or mentee) wanted to become a humanitarian aid worker they would you encourage him/her to do so with some qualifications. So, what I take from that is although it is tough work -emotionally, intellectually and physically- most aid and development workers would recommend this ‘line of work.” Indeed.

For more information on the questions above (and others) I present some quantitative data and offer comment relevant to male-female differences in a previous post.

*********

The next four questions, Q40-43, each merit a detailed examination. The two key questions were “To what extent has your gender been a factor in your humanitarian aid work experience?” and “To what extent has your race/ethnicity/cultural identify been a factor in your humanitarian aid work experience?” Please look for future posts on these in the near future. In a reversal to the sprint of “skimming off the top” here are all responses:

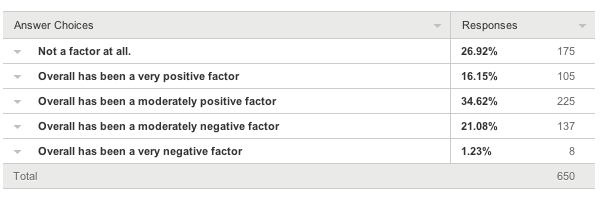

“To what extent has your gender been a factor in your humanitarian aid work experience?”

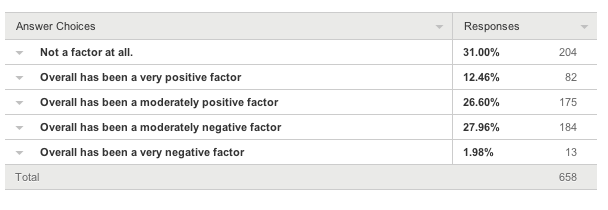

“To what extent has your race/ethnicity/cultural identify been a factor in your humanitarian aid work experience?”

You’ll have to return to the blog later for some of the narrative responses. They are full of insight and contain good doses of humor.

You’ll have to return to the blog later for some of the narrative responses. They are full of insight and contain good doses of humor.

*********

Why do aid workers become ex-aid workers (Q44)? By a small margin, the modal answer was “Burn out: cumulative stress of the job, personal crisis related to on-the-job experiences, etc. become too much to continue.”

Here’s one of many articulate responses:

I don’t think that burn out is the right term but it is hard to both stay authentic to the mission /stay proximal to the problem and also have influence on the big picture (which happens often away from the problem) and also have a safe environment to create and maintain some kind of stable family/community be that a spouse/children or some other kind of modern family. (36+yo female HQ worker)

When asked what they thought their reason would be for leaving this kind of work (Q46), the modal response was “Leave the aid sector entirely to pursue a career in another field.” Again, here is just one of many, many thoughtful and articulate responses, this one from a 30+yo female expat aid worker:

When asked what they thought their reason would be for leaving this kind of work (Q46), the modal response was “Leave the aid sector entirely to pursue a career in another field.” Again, here is just one of many, many thoughtful and articulate responses, this one from a 30+yo female expat aid worker:

“Probably a combination of factors – disillusionment, search for something more stable where I could have a network of friends/family/community, tiredness of endless new beginnings, all of which will probably require pursuing career in another field.”

Questions 47-49 continue the line of questioning about aid workers leaving the industry and will be treated in depth in a later post.

************

So, lots to consider above. In the next post I’ll complete the “skimming” with Part 3. In the meantime, let me know if you have questions or comments. I can be reached here.

Follow

Follow